Ukraine has survived many wars, lost thousands of its loyal defenders and never learned to live with its history. To commemorate the great upheavals and lost lives, we most often erect monuments, sometimes create memorials, and seldom think about how to involve our fellow citizens in the comprehension of this history and living through it, except for laying flowers on a memorable day.

The complex of work with historical memory starting from the usual monuments and memorials to the approaches new to Ukraine is called commemorative practices. Let’s see what these practices are in Ivano-Frankivsk and what monuments in the city could serve as good examples when working now with the losses of today’s Russian-Ukrainian war.

A metaphor of absence

One of the successful modern examples of commemoration in Ivano-Frankivsk is the bas-relief The Wall of Memory of the Heavenly Hundred on the facade of the administrative building of the city and regional councils (that people call ‘The White House’). Its co-creators Volodymyr and Yuliia Semkiv managed to deviate from standard patterns and cliches and create a place that is hard to pass by with no emotions. The memorial was opened on November 21, 2016.

At the passer-by’s level, a bas-relief of human-sized silhouettes is mounted on the facade wall. Above them is an eloquent dedication that reads: “To those who gave their lives for the dignity with which you can look yourself in the eyes.”

The polished steel plate reflects the silhouettes of passers-by like a mirror. In it, you can see your reflection, which is superimposed on the figures of the fallen on the Kyiv Maidan in 2014. Between them, there are quotes from the times of the Revolution of Dignity.

The creators of the bas-relief explain that the materials were chosen in such a way as to establish a dialogue between passers-by and the bas-relief.

“Passing by these silhouettes, we can ask ourselves what those people died for and what we are doing today,” says Volodymyr Semkiv. “Smooth top and bent metal at the bottom, the absence of silhouettes is a drama, it is such a metaphor of absence. The main idea was to make a living memorial that would affect everyone. In addition, we wanted it not to resemble the Soviet ones, not to breathe socialism and to become an example for younger colleagues that something different could be done in Ukraine.

People got used to the fact that a monument is an idol with an arm up or an arm down.”

He says that one of the challenges is to communicate with the tender commission, to convince them that a modern atypical view can be better than the usual standard solutions. In Ivano-Frankivsk, the sculptor Volodymyr Semkiv and his wife, architect Yulia Semkiv, were lucky. The competition was tough, but their project won.

“I think it’s a miracle. We have participated in many competitions. And only ten percent of that was realized. We are pounding this rock,” Volodymyr adds.

The couple continued the trend of monuments that encourage dialogue. In November 2021, a Heroes Memorial by the artists was erected in Burshtyn near the city council building. Three metal stelae with silhouettes of the heroes of the Heavenly Hundred, volunteers and soldiers who died for Ukraine’s independence, are strongly associated with the idea of bas-relief in Ivano-Frankivsk and drastically resonate with the tombstones we are used to.

The idea of the stela in Burshtyn started as a memorial to the Heavenly Hundred, but from the time the project was commissioned in 2014 until its implementation in 2019, it has evolved into a Heroes Memorial to meet the realities of the country.

“The reality is changing, the war has been going on since the Maidan, and the Heavenly Hundred was only the first step in the war for independence,” Volodymyr Semkiv says. “Now is not the time for monuments.

We have to win the war. But I would very much like the talent to overcome parochialism after our victory.

The problem with society in many areas is that people don’t trust professionals and think they know better themselves: they want an angel with a sword and a shield, and there should be more tires at the bottom. Such conversations often arise. To avoid this, the artist must be quite firm and not be affected by such things. Each monument is an artwork. It has to be convincing, to influence people, to make them stop and think.”

Struggle and pain in stone

Volodymyr Dovbeniuk, the creator of the sculpture to the executed patriots in Ivano-Frankivsk, approached the topic of commemorating the dead in an unusual way. It was installed in 2003 in memory of the Ukrainians shot by the German occupiers during the performance of the operetta Sharik by Yaroslav Barnych in the Ivan Franko Theater of Stanislaviv (former name of Ivano-Frankivsk).

Back then the Nazis arrested more than 140 spectators in vyshyvankas (Ukrainian embroidered shirts). On November 17, 1943, 27 patriots were shot near the theater. A list of the names of executed patriots is engraved at the foot of the sculpture. Nowadays, the street is also named in their honor and called the Street of Executed Nationalists.

In his sculpture, Volodymyr Dovbeniuk depicted one of the executed patriots with his hands behind his back and a bag on his head. A significant part of the active residents of the city perceived this piece as vague and waited for the installation of a more eloquent and concrete monument. Fortunately, the sculpture remained unchanged. The unconquered figure of the patriot makes one imagine, ponder and feel empathy. And agree that’s already a lot.

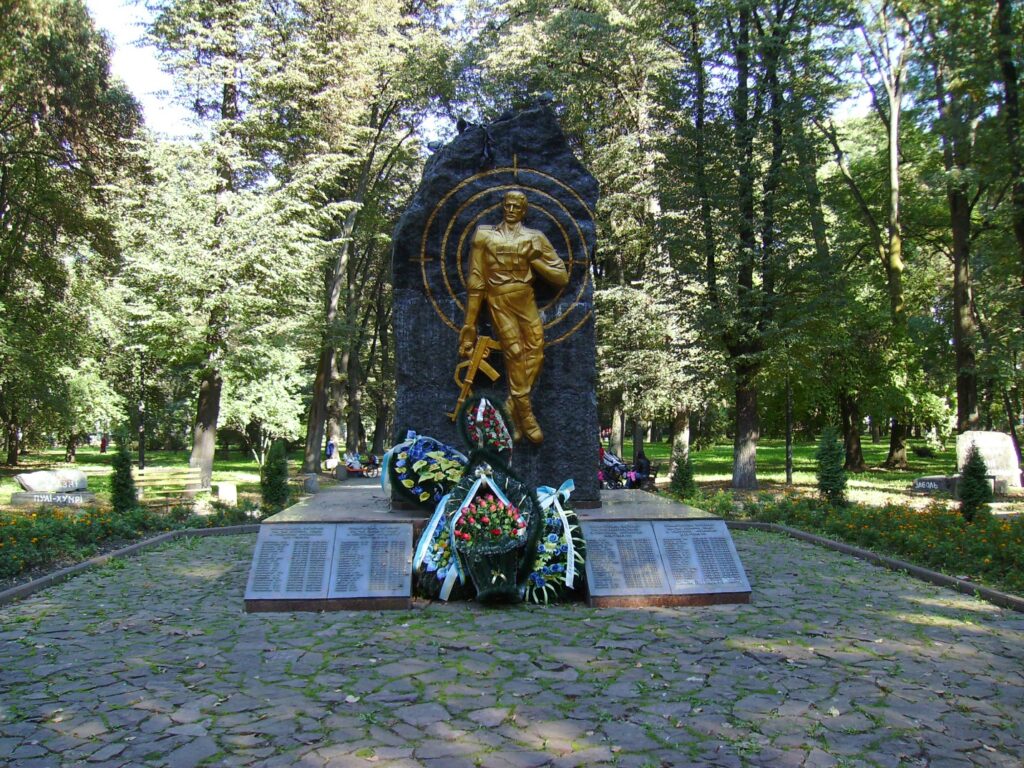

I would like to add one more interesting, though unpopular memorial in Ivano-Frankivsk to my personal top three—the memorial to the soldiers who died in the Afghan war. It was opened to the public in 2009 in the green area on Halytska Street.

The central sculpture is a 30-ton rock with a bronze figure of a soldier standing on it. He is holding his heart pierced by a sniper’s bullet. Around the figure is a sniper scope, and at its foot is a lighted torch carved out of stone and a commemorative table of the dead. Stone blocks with inscriptions in white paint are laid out around it. Those are the names of Afghan cities where the fiercest battles with the participation of Ukrainians took place. The piece was created by Vasyl Vilshuk.

This memorial gives the viewer a choice: either to stay near the main sculpture or to walk past the stone blocks reading the toponyms on them. They can encourage people to learn more about these cities, Kabul, Kandahar, Salang, and Jalalabad, about the battles there, as well as about that war in general.

We are not used to talking about the war in Afghanistan. It is mentioned only by officials on commemorative dates and direct participants in the battles who were lucky enough to survive. Over ten years, 160 thousand Ukrainians took part in the Afghan war, three thousand of them did not come back home. The authorities at the time hid information about the dead in Afghanistan until the beginning of the collapse of the Soviet Empire in 1989. Even now, people are still reluctant to remember this war.

The trauma of the loss of Ukrainians in this war has not yet been spoken about, and in the context of today’s war, this hurts even more. Meanwhile, the Afghan veterans are fighting again, now for our country.

To the heroes of all wars

The only monument from the Soviet times that survived in Ivano-Frankivsk is the Monument of Glory with the “Eternal Flame” and mass graves of soldiers who died during the liberation of the city from German troops in World War II.

It was opened to the public in 1946. Back then, there were also two cannons at the entrance to the memorial. In the center, an obelisk with the “Eternal Flame” inside was placed surrounded by monuments to the Heroes of the Soviet Union, Senior Sergeant Serikov and Colonel Harkusha, on the sides and mass graves of soldiers and officers behind with names engraved on marble boards. Along the perimeter of the fence, 15 stone vases were installed symbolizing the Soviet republics. Later, a sculpture of a soldier with a carbine and a flag was placed in front of the obelisk.

And in 1967, after the cemetery reconstruction, an eight-meter figure of a mother with two children appeared there. The monument was created by sculptors Andrii Lendel and Arkadii Matsievskyi.

Every year, this memorial loses its visitors, and with it, its meaning. Probably, after the victory in today’s Russian-Ukrainian war, it will have to be reconsidered.

It is interesting that there are examples of joint monuments both to soldiers of World War II and UIA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army) fighters in the Prykarpattia region. In 2007, in the village of Torhovytsia, Horodenkiv district, a granite monument of sorrow was erected to those who went through various wars. The sculptor, Serhii Bukhalo, chose a church bronze bell as the basis of the monument.

It is dedicated to fallen soldiers of World War II, participants in the wars in Chechnya and Afghanistan, fighters of the OUN-UIA, repressed, and the Holodomor victims. The names of 40 UIA fighters, 45 Soviet soldiers, 35 people deported to Germany, 26 special settlers and 20 victims of the 1947 famine are engraved on the monument.

And in the village of Krykhivtsi of the Ivano-Frankivsk City Council, a joint memorial to fallen Soviet soldiers and OUN-UIA fighters was opened. It was erected with the money of the community and patrons.

Memorials that are (not) there

World War I is an equally important object of memory preservation for the region. Unfortunately, those events are not so noticeable either in the space of the city or in the Ivano-Frankivsk region in general. However, military cemeteries and burials are also one of manifestations of commemorative practices.

According to the Great War: Graves and Historical Memory project, there are 285 burials in the Carpathian region. The closest to Ivano-Frankivsk is in Yamnytsia. German soldiers of the Reserve Jaeger Battalion No.20 of the 200th Infantry Division of the Carpathian Corps were buried there in 1916.

The modest military cemetery with white crosses inevitably resonates with the memorial to the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen located in the Ivano-Frankivsk Memorial Park. The graves of the 143 Ukrainian Sich Riflemen here are only symbolic because the real burials were destroyed by the Soviet authorities in the early 1980s when the former old city cemetery was turned into a public green area. The crosses were restored in the early 1990s, and the place regained its original significance.

It is no coincidence that 19-year-old Roman Huryk, who was killed in the Kyiv Maidan, was buried here in 2014. After that, several more heroes who died in the Russian-Ukrainian war were buried in the park, which briefly turned into a cemetery again. The last time it happened was in 2016.

Survive trauma and gain history

Since 2014, in Ivano-Frankivsk, there have been no attempts to engrave the events of the Russian-Ukrainian war in the memorials. All the erected monuments relate to the Euromaidan and the heroes of the Heavenly Hundred. However, the commemoration of Ukrainian heroes who died in Donbas takes place on memorable dates. Ukrainian defenders gather near the cathedral, from where, after the memorial service, they march in a solemn procession down the central street to the Memorial Park. Everything ends with a requiem and the laying of flowers there.

With the beginning of the full-scale invasion, several commemorative practices were dedicated to Ukrainian children killed by the Russian occupiers. In Lviv, the “Excursion that will never happen” was organized in memory of the 243 children who died at the hands of the Russians at the time. The commemorative event was held in the Rynok Square. In the empty buses, soft toys were strapped to the seats. Road signs “Attention, children!” were placed nearby in protest against the violation of children’s rights during the war. As of June 12, 287 children are known to have died.

A similar action was held in the central pedestrian street in Ivano-Frankivsk. The memory of the children killed by the occupiers was honored by laying out candles, flowers and more than 200 toys. Later, similar installations were also in the Vichevyi Maidan.

Currently, preserving the memory of these terrible events is mainly done by researchers who publish collections of testimonies about the extermination of Ukrainians, our cultural and material heritage. It is also done by journalists, photographers, and videographers who document the crimes committed by the Russian army in Ukraine. The war is depicted in the works of Ukrainian artists. But now is really not the time for monuments and memorials.

One of the challenges we are now facing as a nation is to preserve every testimony and piece of evidence, reflect on them and then find ways to pass that memory on to future generations. Depending on that we will be able or not to honor all the dead with dignity, learn from our mistakes, and gain and preserve our common values.

Every Ukrainian man and woman who died in the war deserves to be known and their contribution to be respected. But for our future, the value of this memory will be even greater if it goes beyond archives and museums into the public space and becomes closer to everyone.

Memory retention is not just about past traumatic events. Best commemorative practices help survive trauma, place wars in historical context, and encourage public debate. Therefore, it is definitely worth hurrying with it.