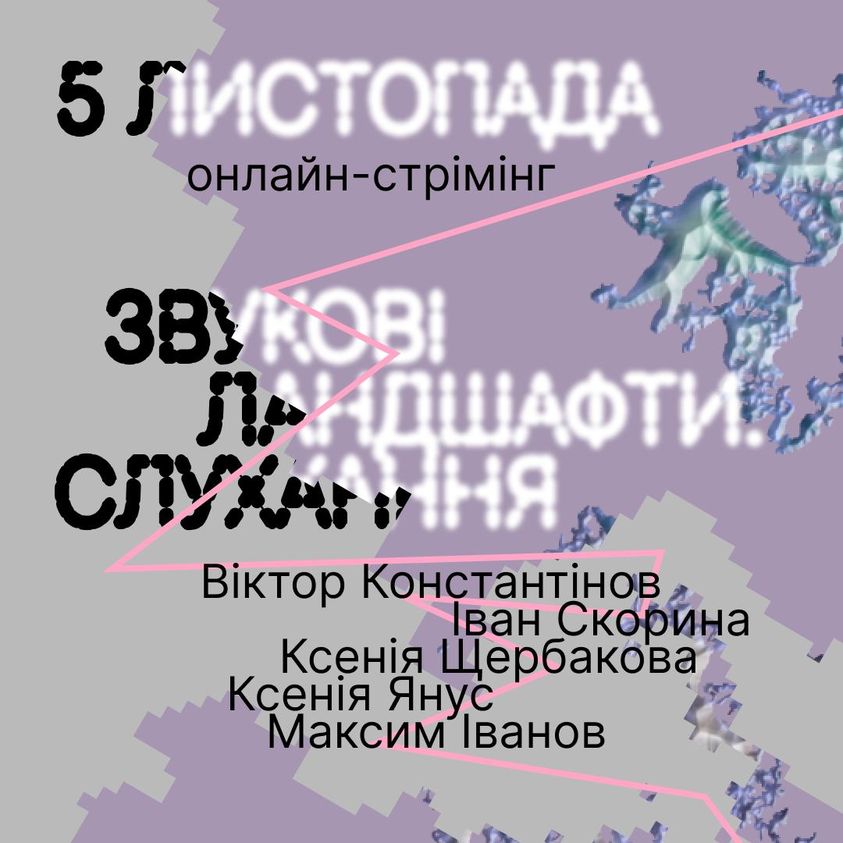

Yuliia Manukian, an art critic and historian, tells about experience of five artists, who in November 2022 shared their observations of soundscapes of five Ukrainian cities, from Dnipro to Uzhhorod.

One day, I went on sound journey Soundscapes. Listening in the framework of the laboratory Land to Return, Land to Care.

Cooperation of artists from Ukraine and the UK resulted in a twelve-hour live stream, mixed in London. The stream is a part of the lab, initiated by The Museum of Odessa Modern Art together with NGO Slushni Rechi and cultural memory platform Past / Future / Art. The partners of the project, Soundcamp arts cooperative and Acoustic Commons project, developed methodology of work with live sound in real time. Usually, they install their streamboxes, portable open microphones that relay sounds to an online map, in places of environmental or cultural importance. That’s why these devices are frequently used by environmental activists at environmental forums or protests, or those dealing with cultural heritage.

Natalka Revko, a co-curator of the project and head of Slushni Rechi, says she offered the project to the Museum of Odesa Modern Art before the full-scale invasion.

‘My idea was to create a sound lab, focusing on environmental issues in the Black Sea. We had a long-term plan to install streamboxes in the landscapes we were losing, on the Kinburn spit and in one of the ports of the Odesa region.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine made us change the concept. We wanted to respond to what was happening here and now, and to expand the scope and geography. I invited curators from cultural memory platform Past / Future / Art Oksana Dovgopolova and Kateryna Semenyuk to develop a new vision of the project together. That’s how we ended up with reflecting war experience and environmental impacts of the war.

We changed the concept and approach to sound. Two things were important for us when we discussed the location of streamboxes with British partners from Soundcam and Acoustic Commons: 1) not to select a location in advance to ensure mobility of projects by marking a number of places on the Ukrainian map; and 2) to document different experiences. When we offered musicians to participate, we wanted to expand geography as much as possible with due regard of accessibility. Some artists, we are working with now, have experienced displacement. For instance, Maksym Ivanov from Kryvyi Rih is now living in Dnipro, Kseniia Yanus from Donetsk had to move to west of Ukraine, while Kseniia Shcherbakova, who lived in Odesa in recent years, to Lviv. Ivan Skoryna remains in Kyiv, and Viktor Konstiantinov in Odesa.

We had a weeklong workshop with British partners and co-curators of the project in September. That was an important part of the project. We learnt how to use devices to relay sounds in real time. The partners sent us all the components, and the participants assembled streamboxes themselves to better understand what the black boxes consisted of and how they became communication media. Five initial streams laid the foundation of further publications. I’d recommend to listen to them too (in the archive) to gain the impression of the present sound texture from these valuable stories’.

Sound is the message

I’d like to narrow McLuhan’s famous maxim ‘The medium is the message’ to our subject. It’s not new. There are sound labs and individual researchers that work with soundscapes during war conflicts. Such studies provide interesting comparative material that contributes to a better understanding of a specific historical period.

Authors of the article Sound Matters: How Sonic Formations Shape the Nuclear Deterrence and Non-Proliferation Regimes hope that ‘by developing a conceptualization of sound as a social phenomenon and tracing its connections to relations of power’ they could define ‘the types of sonic “data” that constitute and affect our social and political worlds’, and how ‘sonic formations… may contribute to the dynamics of violence, accumulation, domination, resistance, and diplomacy’.

They also add that ‘sounds were at the heart of many stories about the war experience. They were also a source of the physical and psychological scars soldiers brought home with them as well as the attention paid to sound and noise in post-war societies’.

Sounds of War and Peace Soundscapes of European Cities in 1945, Renata Tańczuk / Sławomir Wieczorek (eds.) is one more example of such a transdisciplinary research.

It is a comprehensive study of urban soundscapes in 1945, covering such areas as the following:

- the soundscape of air raids and bombings;

- silence and noise in the sound environment of ruins and empty spaces;

- ‘attentive listening’ in cities fraught with danger;

- sound and trauma;

- musical creativity;

- the sonic aspect of Victory Day celebrations;

- the de-urbanisation and rusticalisation of the soundscape of destroyed cities: they may grow increasingly still and empty, as if gradually returning to a simpler past, not as crowded or as noisy;

- the sound environment of post-war reconstruction;

- the sonic indications of a return to normality;

- The constant and changing sounds of propaganda – from Nazi to Communist propaganda;

- sound technologies (radio, broadcasting centre, street loudspeakers);

- the transformations of national acoustic communities;

- the adaptation of unfamiliar urban spaces through sounds;

- the ways in which the soundscape of 1945 was represented in literature, autobiographies, feature films, documentaries, exhibitions and musical compositions.

Photograph of the Altstadt. 1945. Photo by Richard Peter

Ideas of Joy Damousi, a Professor of History in the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies at The University of Melbourne and Chief Investigator on the research project ‘Hells Sounds’ shed more light on the topic. The project aims to re-conceptualise the history of the two world wars through the auditory landscape created by inflicting violence on the senses. The researcher is interested in how sounds of the battlefield and the home-front have shaped the experience and memory of these events by civilians and combatants. Professor Damousi is trying to merge military history with cultural history to look at a broader spectrum of wartime experience and capture different experiences of war and its legacy. She believes research in this area is vitally important, particularly in the context of how the body and senses are affected by these moments of extreme violence.

‘Sound is so embedded in our memories; that’s what people retain, the auditory impact, even in our contemporary digital world that is saturated with images. We need to look at our responses and how medicine has or has not caught up with those sorts of connections (between sound and emotional impact)… We can’t really write about ourselves, in the present or the past, without looking at issues around sound and listening’.

The project Soundscapes. Listening focuses on ‘mutism’ of war, where the voice of everyday life is dominant. However, recordings of specific sounds alone are not enough to understand, how people perceive and assess certain soundscapes. That’s why artists provided descriptions to explain origin of sounds and their personal feelings.

Sense of isolation and inability to communicate with friends, colleagues and relatives are among sensitive topics for all artists. When listening to these streams you find yourself in a certain sound environment and a sound world. It seems, there’s no physical distance between an artist and you. Such a tangible feeling of togetherness.

This is the first time I experience anything like this, as well as our artists, most of whom are musicians. It’s rather challenging to work with a raw audio. There’s no way you can clean up or process it, or create a dramatic composition. All you can do is to stream. In the end, you start to understand sound structures though. Everything is informative: what appears to be a fault; disrupted communications; the so-called ‘noise’, which is usually out of your focus; the muttering of voices; and the general backstage vibe.

This is how I find myself inside the project consisting of five circles of stream diving. I slowly swim, sink, emerge or meditatively sway on the waves of someone else’s, ‘technologically’ packed, confession.

12 incredible hours of listening experience

I’m in Intourist-Zakarpattia Hotel, Uzhhorod at the Sorry No Rooms Available art residency, listening to the first stream, Autumn Excursion by Viktor Konstantinov, a musician from Odesa.

It’s a very different Odesa. The war ‘devastated’ the city and deprived it of tourist hype. ‘The city has become disturbingly silent. Usually distressing noises of traffic jams, crowds and other outdoor sounds are just a melancholy memory’.

The routes Viktor has chosen for his city tour at first glance have little to do with the popularised image of the city: the Cossack cemetery of the Sotnykivska Sich dating back to the middle of the 18th century just outside of the city; a ride on no. 20 ‘reed’ tram to the downtown; Marynesko Descent; a graffiti wall of the Odesa Fine Arts Museum (from where Viktor and his friends helped evacuate artworks at the beginning of the war); the house in 52 Pastera Street, where Viktor spent the first months of the war and where Ukrainian People’s Republic activists Ivan and Yurii Lypa lived in 1917-1918; the ‘star’ of the nearly forgotten poet and writer Borys Necherda on the Alley of Stars near the Opera House.

A tram ride

When he mentions poor connection because of shelling, I suddenly hear an air raid alert. ‘Suddenly’, because it’s uncommon here. This coincidence, my reality superimposed onto Odesa’s reality, which is documented here and now, is so symbolic. Everything is symbolic now, in these ‘apocalyptic’ times, when you’re as good at seeing and interpreting signs, as seers of the past.

I’ve just arrived from Odesa, and it’s all very familiar to me.

There’s an ambulance siren both there, in Odesa, and here. Everyone seems to hate it now, because it gets on our nerves. This sound causes distress during the Odesa walk, even though it’s a peaceful sound, after all, albeit an alarming one.

The stream is suddenly interrupted, the silence hurts my heart: is he dead? Death, however, is no longer something unexpected. On the contrary, it makes me wonder, why I’m still alive, if he reaps so many crops.

At the same time, I hear my friend asking me,

‘How do you recharge your mobile, for one month?’

‘For about three months, not to bother. I used to buy an annual plan, but I don’t do it anymore. There might be no tomorrow, so why pay extra’.

It’s also a sign of the times. It’s our excuse: How can we plan anything if we’re not sure we will survive until tomorrow? At this very moment, the artist gets to the cemetery. I can feel the breath of eternity, commemorative ‘beauty’ and Thanatos’ realm. The noise of city traffic fades, and the crunch on gravel (or whatever material they use to make walkways), on the contrary, becomes louder. It’s so real, as if I’m walking beside the artist.

The Cossack cemetery in Odesa

I listen to urban cacophony and try to make a comment to Nikita’s Kadan Resistance Movement Museum exhibition. Artefacts for it were found at Svyniachka, a spontaneous market in Radvanka [Author’s note: the Roma neighbourhood in Uzhhorod.] By the way, David Chichkan and I had an interesting experience there. It’s a quiet place, there’s no sign of Roma’s boisterousness. This is how stereotypes are broken down. Everyone is calm there, even wary, since the war has affected us all. This is one more touch to an overall soundscape. Some Roma left for army. David drew their portraits using photos as a reference. He then turned drawings into posters and gave them to servicemen’s relatives.

Kadan’s exhibition is not so much about the museumification of the subject series as the museumification of ‘transgressive’ experience of mental resistance against the background of physical opposition, as well as about how they correlate in a ‘lightning-fast’ changing environment.

‘War alters bodies, habits, tones of voice and thinking. Bones and organs can be mixed with glass and concrete in a matter of seconds. The rapidly changing situation creates new traps for conformal solutions. Thought resets the relationship with the idea of the future. Body experiences continuous adrenaline infusions… Museum is about ‘making war history’ in real time. Museum has a capacity to preserve peripheral narratives, and peripheral life. Museum, however, is also a trial…’

How clearly everything fits into the concept of instant museumification of the surrounding manifestations of resistance, including through sound projects.

Viktor walks past a graffiti wall of the Odesa Fine Arts Museum. There are so many memories related to this place. The latest and the most vivid impression is the Before the War exhibition, opened after a missile hit the port causing window damage in the museum. I was struck by the audacity of the gesture, administrative and curatorial. It made me think again about beneficial in art, about our obsession with eschatology during great turbulence. And this ‘I knew it would happen!’, when the Agamben’s ‘suspended’ messianic time did explode as another ‘radical crisis’.

Graffiti on the wall of the Odesa Fine Arts Museum

Suddenly I hear Viktor telling a very interesting story to his friend, artist Sana Shahmuradova. I strain my ears, but everything is in vain, his voice is barely audible, I can make out only few words. It seems it’s about some writer. It’s annoying, I’m intrigued after all. A little later, I ask him to solve this mystery.

‘During the war, I discovered work of Borys Necherda. Around 1.5-2 years ago, while living in Kyiv, I started wondering who represented Odesa in Ukrainian literature. There are many Russian-speaking writers, while we should still search for Ukrainian-speaking ones. That’s when I came across Necherda in some list of Sixtiers. I didn’t look in more detail. I can’t say there was little information, but some research was needed. I got interested again in spring 2022. I remembered about him and decided to read his poems. They turned out to be quite good. I found he had written a lot of prose (Wikipedia says he has only one novel, but he wrote three of them in fact; I mentioned his novella September, October, November during my tour).

I ordered his books, and I’m still reading them. I was impressed by high quality of his language in prose and poetry, as well as his destiny. He was a Ukrainian-speaking nonconformist poet, living and writing in mostly Russian-speaking Odesa in the 1960s-1990s. His legacy is interesting and coherent, although he was hardly recognised during his lifetime. He posthumously won the Shevchenko Prize and got a ‘star’ on the alley in Odesa, where he’s now almost forgotten. His star became one of my personal markers of Ukrainian identity in the city’.

Borys Necherda’s star

There were several such explanations during the tour. I’d like to add that it was the only stream, where they were important. Unfortunately, I couldn’t hear them well and it still upsets me.

Viktor and Sana continue their walk. Suddenly, the monotonous city noise is broken by a woman saying, ‘My son was taken for surgery’. There’s again a bunch of my own flashbacks and thoughts about other people’s sons, who are now at the front or in graves. I feel sad. And here the next stream starts.

Through the Centuries to Peace: Serednianskyi Castle

A project by musician Kseniia Yanus, who was forced to flee her hometown of Donetsk in 2014. ‘I was born 1,500 km from where I am now. The Russian invasion forced me to move from the Eastern border of Ukraine to the Western one. Donetsk–Uzhhorod–Odesa–Užice–Benešov–Odesa–Uzhhorod, this is my route of the last 8 years. The route to find my lost home, safety and peace. Uzhhorod is my guardian city, my usual shelter in the face of impending rockets, shells and military vehicles. Anxiety, which is always my companion, which lives inside me and permeates everything I write and create, wonderfully contrasts with the peace and leisure of Transcarpathia’.

Serednianskyi Castle

Kseniia’s music is rather hard. The fact she was born in an industrial region affects her artistic path. ‘The central themes of my art are alienation, internal migration and reflections on the experience of childhood in the industrial region of Donetsk. My music is multi-layered, full of noise, glitches and disturbing synth parts’.

She wanted, however, to spend some time in a peaceful environment, even though that sense of security was rather fragile. Her stream is an island of silence, not alarming, but peaceful. First, I was expecting some twist. I was wrong.

There are barking dogs, crowing roasters and chirping birds. Peasant pastoral and magical silence of ruins. Mutual indifference of humans and heritage. We allowed it to fall apart, and it will contemplate our demise indifferently. We share a somewhat common fate, only the pace is different: it’ll take a while for the ruins to dissolve in time and space, forming an interesting archaeological layer for future researchers, and we’ll become just compost. I thought of architect Hundertwasser, who wanted to be buried in an open coffin with a tree planted on top. This is, however, about voluntary transition to a fertiliser state, while we are facing violence and genocide.

I also liked Kseniia Yanus’ workshop project Rotunda – Church Shelter, because I couldn’t but visit this beautiful landmark, painted in fresco, according to popular belief, by Giotto’s students in the 14th century. Although not a religious person, I understand why people look for peace, mental and physical, in such places.

Rotunda Church

During our visit local priest, father Bohdan Savula, congratulated everybody on the liberation of Kherson. He commemorated fallen soldiers, asked parishioners to help residents of Kherson, facing a humanitarian disaster. The war and its impact are everywhere, you cannot hide.

‘When I thought about a soundscape I want to relay, I first though about the industrial landscape, I’ve been used to since my childhood. That is, to transfer the memory of sounds from Donetsk to Uzhhorod, where I am now. The main sound is the hum of the Donetsk metallurgical plant. Deep and repulsive, it could be heard throughout the city. You could guess what time it was right away: while some people were returning home after hard work, others were only heading there. They went to work that in fact was killing them.

Then I wondered, what interesting sounds could be recorded in Uzhhorod, and eventually moved away from the idea of an industrial soundscape. I chose a calm area, the Horyanska Rotunda. I was attracted by the fact that it’s a historical place that used to be a part of different empires. This sacred place of strength for many people is now a haven of peace, hope, and prayer. Here people remember the dead and pray for the living. There’s a view of Uzhhorod’s industrial area from the hill. This spot allows me to look at the place where I came from (the industrial landscape I’m used to) and to be safe at the same time. During the stream, there was the echo of that industrial area and the sound of airplanes or drones, but two dogs were playing near me. The service began. The atmosphere was incredible. I came out of natural sounds and plunged into beautiful chanting right away. Unexpected transition from silence to praying. The stream turned out to be so atmospheric that my husband and I now chop samples, sounds of the service, for our album’.

About silence at war

Silence also conceals traumatic experience. Nine months of war taught us to respond to sounds, since it’s critically important for our survival. We learnt to distinguish the ‘subtleties’ of the air raid alert system: continuous tones, amplification and attenuation, sinusoidal 200-400 Hz oscillations, interrupted by a pause. The same is with types of artillery. We can call it a syndrome of acquired sound sensitivity. Our anxiety, in fact, also evolves.

In the first days, we were paralysed with terror or instantly threw ourselves on the floor face down. Today we are much more restrained in our reactions and quickly define the level of threat by sounds.

Silence is also a multi-layered soundscape. For example, silence on the battlefield is literally the calm before the storm. Joy Damousi says, ‘soldiers were writing how that was more terrifying than listening to bombs and artillery. They knew exactly where they stood when there was gunfire, but when there was silence there’s extraordinary fear and heightened anxiety about what is coming next’.

Such a juxtaposition of noise and silence shows the paradox of the frontline experience during the conflict: on the one hand, eerie silence, and on the other, the cacophony of industrial warfare. Sound Matters: How Sonic Formations Shape the Nuclear Deterrence and Non-Proliferation Regimes also contains an example of the ending of the First World War. For combatants on the western front, the noise of four years of terrible violence was replaced by a quieter soundscape when artillery barrages ceased at 11:00 am on 11 November 1918. The sonic dimension of this transition was recorded by a single sonograph. Entitled The End of War, it captured acoustics in the minute prior to cessation of hostilities and in the minute that followed. Researchers are surprised that no audio recordings of the frontline exist, even though audio recording technologies were readily available.

When I read about 11 November 1918, I was struck by the coincidence: Kherson was liberated on 11 November 2022.

The next journey makes me face (listen to, to be precise) a specific problem. The project by Ivan Skoryna, a musician from Kyiv, is not only about honouring a hero, but also about ‘atonement’ of his own imperfection. ‘This memory of my own naivety and the shame I felt for being indecisive caught up with me this summer under unusual circumstances. On June 18th, we said goodbye to Roman Ratushnyi on the Maidan. This is the first time I had knelt in front of a coffin, putting flowers on it and touching it, bowing my head. I heard, the voice of Roman’s father, trembling with suppressed tears’.

Please follow the hyperlink in the title to read the whole story. I will only add that such commemorative gestures are ‘louder’ than all pathetic speeches.

Ivan walks along the streets of the city to put flowers on Ratushnyi’s grave. I recall everything connected with this name, and think of Roman’s feat and the sadness that engulfed the country. Once again, I cannot accept that, as in previous wars, the real cultural, artistic, intellectual elite, young idealists are the first to go to the front. They either die or become disillusioned, like the ‘lost generation’ after the First World War. There is a difference though: our people won’t be like that, since there’s no ‘What do they give their lives for?’ There’s only bitterness of the price we pay. No matter how cynics devalue the ‘moral imperative’, there are those for whom it’s the only life compass. I think of Anish Kapoor’s note at his art show in the framework of Biennale 2022,

‘War is won not by pain inflicted, but by the pain that can be suffered’.

City noise, clamour of voices, laughter, shuffling feet, clattering heels, someone whistling a familiar tune, sighs, birds, rustling cellophane (perhaps someone’s unwrapping flowers). Silence.

photo by Dmytro Lykhovyi / Novynarnia

As a part of the workshop, Ivan Skoryna created an illustrative project Digging Day. There are iconic autobiographical accounts of life in trenches that show how closely war experience is linked to certain sounds. However, the sound of digging trenches can be included in the list of ‘dominant’ not only on the front line.

When the war started, Ivan joined a group of volunteers that was helping the territorial defence forces. He dug a fictitious trench intended to distract attention from the main position of the territorial defence unit.

‘I dig the fake trench and think of those who are digging real ones. Where are they now? How did they get used to military life? Are they tired? How many trenches have they dug by now? How often do they pick up a shovel to care for the land we are protecting in such a literal way?’

The situation has changed, and Ivan is no longer involved in volunteering. However, ‘that practice of digging trenches remains with me as a fresh memory’. That’s why specially for the workshop, Ivan went to the same place and recreated the day of digging the trench. How long will he associate the knocking of a shovel with the greatest threat to his hometown, and more broadly, with war? Perhaps, the whole life. Maybe someday this connection will be weakened a little, or significantly, by sharper sensory ‘scars’.

When I start listening to a stream of the DIY culture festival Chvert [Quarter], I can hear electronic groove from Porokhova Vezha [Powder Tower].

This is a project by Kseniia Shcherbakova, the most active streambox user. She streamed audio from a festival that she organised together with her friends and the creative community. ‘Our activities were greatly affected by the fact that many of us were forced to relocate. Most of the established connections that were formed in physical spaces have been destroyed. But these broken connections have become the basis for new, DIY methods. This stream is about each of the artists and participants, and their experience of work after the full-scale invasion. Many within our community have changed their activities: most are volunteering, while others are trying to relay their war experience and thereby help themselves and others to survive it.

poster by Illia Todurkin

It is about overcoming the feeling of alienation and isolation that can drive you crazy. Kseniia made a stream for the workshop in the form of a diary telling about her trip from Lviv to Odesa by night train with the following message,

‘This work is dedicated to all those who have been parted with their loved ones and feel distance in a physical and emotional sense. I suggest you get on the train with me and imagine how we overcome this distance together’.

It’s poignant, because I know this feeling too well.

The stream is long, it lasts until 11 p.m., that’s why I accept an invitation of street artist and photographer Eric ‘Cuba Cube’ from Uzhhorod to go to a photo exhibition in Café Libertad.

The black-and-white chronicles of parties seem to be good, but you cannot see them well, people are eating and drinking there, and everyone slowly moves onto the terrace in front of the café. Those who are really interested demand from the artists and the curator to tell something about the meaning of the event, there is a courageous, but too rapid attempt to make a curatorial statement. The audience is a bit disappointed, but they make do with what they have: the party continues, in the atmosphere of the ‘00s and with the nostalgic charm of flashbacks.

I get back to the stream from Lviv. Somebody asks me, ‘What are you listening to?’ ‘Life’, I reply honestly. I come back home to listen to…

Indoor Concert from Dnipro, recorded by musician and composer Maksym Ivanov during the curfew.

If I had to choose a soundscape that is an example of unbearable pain and broken life, that would be Indoor Concert.

Solitary tapping on the keys is a rather mesmeric and depressing experience. Nails of hopelessness are hammered into the heart with every sound. There’s no trace of the carefree evening left. Elevated spirits are erased. I’m even a little angry to have such a stream at the end of the day. The poisonous text, however, is already running through my veins, because I know everything about the oppressively dead silence and its saving ‘oblivion’ for crushed nerves.

‘Now the door of my apartment is tightly closed and heavy curtains hang on the windows, blocking the light and absorbing the sounds of the street. Only in this oppressive dead silence I feel safe. I am sitting on the cold, dirty floor of my dark apartment, working on a chamber concerto. A chamber concerto so tiny it can only accommodate one person. A person who performs this concerto only for himself. Outside the window are my beloved October and the empty eyes that still wander the streets in search of something…’

This is a pure experiment: How long will you listen to other people’s streams? Will you be seduced by the game of two ‘worlds’ merging? There is a great deal of performativity here, not only on the part of the artists, but also on the part of the listeners, if they are inclined to it. This is achieved through a whole range of diametrically opposed emotions, like Skoryna putting flowers on Ratushnyi’s grave and Kseniia organising a festival. This may hurt; someone can be taken aback by such a mix. This is, however, our reality. We honour the fallen and attend cultural events. This is the best manifestation of our invincibility, which makes us even stronger.

I believe that not only our successes on the front, but also the rejection of the victim image, clearly articulated at the world level, would mark the turning point in this war. Melancholy prevailing throughout the day of listening would kill the very essence of the idea.

Films about war use effects that literally bombard their audience with sounds. The real soundscape has a far more complicated structure and can tell much more about the reality of war. In her essay Barking and blaring: City sounds in wartime, Annelies Jacobs, a lecturer at the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences of Maastricht University, notes that

‘One way to gain access to the blankness or confusion caused by war is to consider the sensory experiences of everyday life’.

Participants: Viktor Konstantinov, Ivan Skoryna, Kseniia Shcherbakova, Kseniia Yanus and Maksym Ivanov.

Partners: Museum of Odesa Modern Art, NGO Slushni Rechi, cultural memory platform Past / Future / Art, SoundСamp arts cooperative and Acoustic Commons project.

The project ‘Land to Return, Land to Care’ is supported by the British Council as part of the UK/Ukraine Season of Culture — ‘Future Reimagined’.