Olesia Saienko is a photographer and visual storyteller. She was born in Lutsk, and lives and works in Ivano-Frankivsk. Olesia is engaged in documentary and conceptual photography. Her practice is centered around the themes of post-truth, memory, and manipulation in photography, which is a logical extension of her journalistic work. After receiving a scholarship from the Lithuanian Council for Culture, she began to implement a project in which she reproduces photographs of people repressed by the Soviet authorities. We spoke with Olesia about historical memory, families affected by the Russian Empire, archiving, crime, and impunity.

How did you become interested in photography?

It was my hobby as early as school times, but back then it was more like a childhood hobby. Later, I volunteered at the press center of the academy where I studied. I was impressed by photojournalism and reporting work. And then I gave up everything — until I went to a psychotherapist at the age of 25 and decided to return to my primary dream. Since then, I have been professionally engaged in photography.

You grew up in Lutsk, but now you live and work in Ivano-Frankivsk. Why did you decide to settle here?

It is actually very difficult for me to answer the question, “Where am I from?”. Because I was really born in Lutsk, but I do not identify myself with this city — it is just the place of my birth. Then I lived and studied in Ostroh for five years, and then I returned to Lutsk. I lived in Lviv for a while, in particular, I saw the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic there. But I never liked Lviv, so living there was a certain challenge and a compromise in married life on my part.

Now, we have moved to Ivano-Frankivsk, and my husband must compromise. I really wanted to live in this city, because I knew about the Stanislav phenomenon and it was interesting to me. I was drawn to Ivano-Frankivsk like a magnet. It seemed that moving here could be productive for my creativity.

Did your hopes come true? Has Ivano-Frankivsk given you space for creativity?

It has. I immediately started looking for creative opportunities as soon as I moved here. I am currently working on a project that is not related to repression, and it could only be implemented in Ivano-Frankivsk. The city itself inspired me for this project. This is a pseudo-documentary story about a vampire. It is based on an urban legend, on the one hand, and on propagandistic Russian reporting, on the other hand. It says that a vampire supposedly lives in Ivano-Frankivsk, who rises from the grave and kills girls. The project is still in progress, so I don’t want to fully reveal the intrigue, but I can say that it could only take place here, in Ivano-Frankivsk.

Then let’s talk about your project Reflection on Repression. Within it, you reproduce photos of people repressed by the Soviet regime by photographing their descendants. You started doing this project in 2019, didn’t you?

Not exactly. In 2019, I just got the idea. The first archival photo I saw was a photo of my husband’s great-grandfather. He participated in World War I. The photo was taken while he was a German prisoner in Strasbourg, however, looking at this photo it was hard to tell that: he looked like a noble man. I liked this photo visually and wanted to recreate it, now photographing my husband. But on a subconscious level, I felt something deeper — an opportunity to show how history repeats itself. This is how the idea of the project began to take shape.

Kyrylo Tarasenko and his great-grandfather Arkadii Brahinenko who was shot on October 10, 1938, two months after his arrest, in the Berdychiv prison by order of the NKVD on a fabricated case. He was rehabilitated on December 10, 1957, due to the absence of a crime, after numerous appeals by relatives.

I tried to start working on the project back in 2019, but it seemed very difficult. It was necessary to look for people, who in turn had to look for archival photos — not everyone has the time, resources, and desire for this. In addition, these people are scattered not only in Ukraine but also all over the world, so it is not easy to find them. But after February 24, 2022, I went to Lithuania, for a residency, and decided to start working on this project anyway. The fact is that Lithuanians were also experiencing repression — however I naively thought that it was only us, Ukrainians, who were so unhappy — and the Lithuanian Council for Culture allocated me funds for a scholarship. This allowed me to get started.

It seems to me that now people are more willing to participate in such projects. Everyone is trying to work for the Ukrainian victory, and I want to believe that this project also brings us closer to it. After all, it shows Russia’s crimes, shows that the perpetrators of these crimes were not punished, and in particular because of this, Russia continues to commit them. By Russia, of course, I mean the empire, the Soviet Union, and today’s Putin regime. It’s all one big cluster of evil.

In your Facebook post, you said that your grandfather was shot by the security forces (NKVD). Could you tell this story? Have your family archives been preserved?

My mother told me this story. As it turned out, in families, people didn’t talk much about such topics because they were afraid. My great-grandfather’s surname is Rykhlinskyi. Apparently, he was a Pole. As we know, in Volyn Poles were exterminated by people of different nationalities, so my family could not trust anyone. Once my great-grandfather came to Lutsk, he was caught and shot without charge or trial. This terrible punishment was not just illegal. Moreover, it was absolutely unclear why he was killed. Later, a mass burial was found on the territory of the old city, where the monastery is now located. My great-grandfather was among those buried. We have not a single memory left, not a single photo, because all archival documents were destroyed.

Documents and photographs of repressed people were often destroyed. How do you now find archival photos and people who are ready to share them?

It is like a spontaneous process of collecting photos. Moreover, I think that I have a detective alter ego. At first, I looked for people through social networks. But often my acquaintances shared their stories with me in private talks. At the same time, many did not consider their ancestors repressed, because they understood only executions by repression. Just recently, a friend of mine told me about her relatives: «They were just dispossessed as kurkuls. This is not exactly repression». Like, they weren’t killed, they weren’t sent to Siberia, and that’s fine. They also say that «my relatives survived the Holodomor miraculously». But the Holodomor is also a repression, one of the most terrible ones.

I think this kind of perception was formed in us due to the fact that we were taught a distorted version of our history for a long time. And history, as we know, is written by the winners. This deformation can still be traced: some people were genuinely surprised that the «fraternal people» attacked us. It’s like Stockholm syndrome. People suffered from terrible repressions, but they still cried when Stalin died. And not only him. For example, Marina Abramović describes in her book Walk Through Walls how she mourned Tito’s death. That is why it is important to learn true stories in order to see the reality that is not distorted by propaganda. This would help us better prepare for this Russian full-scale war against Ukraine.

Before starting work on the project, I consulted with a historian. He advised dividing the history into periods, focusing on certain years of repression, or singling out fabricated accusations or those that corresponded to perverted Soviet legislation. The latter include, say, arrests and executions for cooperation with the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA). But I decided to talk about everything at once. I want to show the large scale of these criminal acts and, so to speak, their diversity. If there is a story about repression in the family, it should be told.

Backstage from the shooting, August 2022, Lviv. The photo features Yevhen Dementiev whose great-grandfather Nykyfor Reklytskyi and his family were dispossessed as kurkuls by the Soviet authorities. And also, Dmytro and Artur, who help hold a blanket as a background

What descendants’ stories do you remember the most?

I was most impressed by the stories of the Lithuanians. Their legacy of pain was new to me. I found out that they had their kind of the UPA called Forest Brothers. Relatives of many of my respondents were members of the Forest Brothers. Some were dispossessed as kurkuls, some were taken to Siberia. I was struck by the fact that almost every railway station in Lithuania has a commemorative plaque, on which it is stated that mass deportations of Lithuanians to Siberia took place there in 1945-1947. It seemed to me that this was a very correct approach to historical memory. Apparently, they still haven’t forgotten the evil that Russia did to them. Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion of Russian troops into Ukraine, Lithuanians have always been the first to advocate the recognition of Russia as a terrorist state and actively collect money for Bayraktars.

I was also surprised that Germans, Jews, and Poles participated in my project. There is even one Russian. His family was also repressed. And this suggests that it is not a matter of nationality, but of a regime, a system that must be destroyed. After all, we must admit that there were Ukrainians and Lithuanians in the NKVD as well. One Lithuanian from my project was informed on by his compatriot. He was one of the Forest Brothers. At her prompting, the man was surrounded by people from the NKVD, and he was forced to shoot himself to avoid being captured.

Are people willing to share their stories or are they still in pain with it?

In fact, many of the young people are introduced to these stories for the first time with me. They ask their grandparents. One guy has the diary of his grandfather who was in the UPA. He just now started reading it, researching it, studying it, and writing this story. And, for example, another participant, a woman from Lithuania, reluctantly talks about her mother, who was sent to Siberia as a child. I think this is a difficult topic for her.

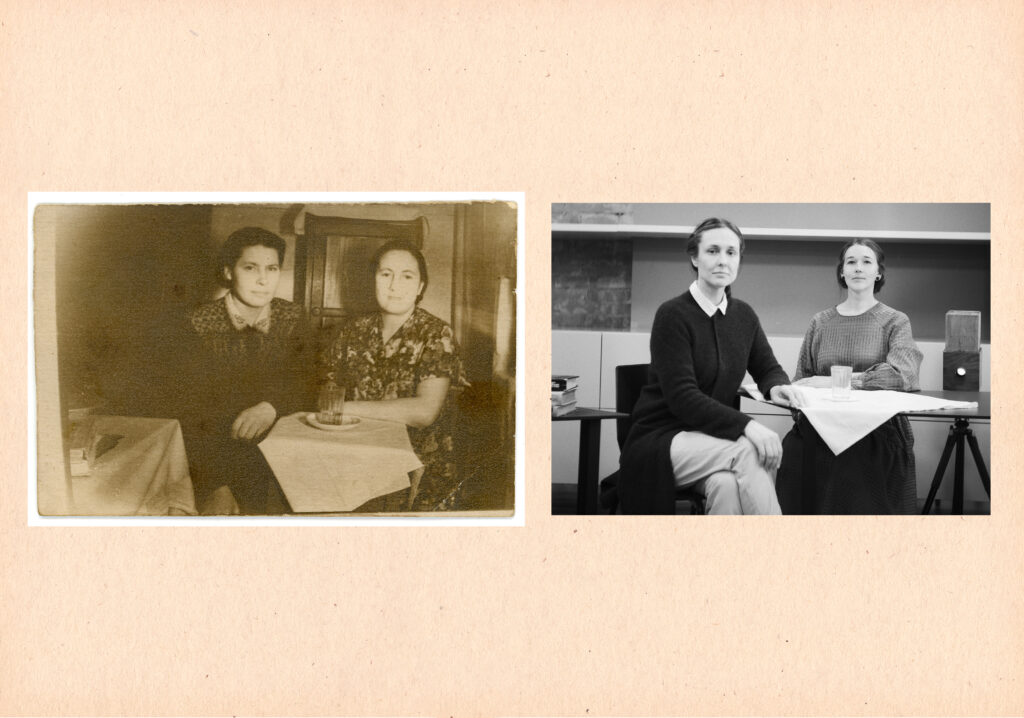

Sigita Kupscytė (on the left in the second photo) and her grandmother Petronėlė Kuraitytė-Stonienė-Stosienė (also on the left). Petronėlė grew up in the beautiful area of Raseiniai, in Lithuania. Her parents, Povilas and Juzė Kurayčiai, were farmers and owned 20 hectares of land. When the Soviet authorities returned in 1944, Petronėlė’s two brothers joined the partisans to avoid serving in the occupation army. In 1946, the NKVD arrested Petronėlė to find out where the partisans were hiding. She managed to escape and join her brothers. She belonged to Juozas Stonys’s detachment of the Kęstutis Partisans Military District. Petronėlė’s two brothers and husband were killed. While pregnant, Petronėlė left the partisan movement and adopted a new name, Ona Blankytė. In 1950, she was caught, arrested, and sentenced to 25 years in the Gulag and 5 years of exile. She had to leave her one-and-a-half-year-old son. In 1951, she was brought to the Gorky (Nizhny Novgorod) prison, and soon transferred to the correctional labor camp of the Bratsky district of Irkutsk city, then to the correctional labor camp in the Kemerovo region of Siberia. Petronėlė returned to Lithuania in 1958.

How would you describe the main goal of this project?

Firstly, it is the restoration of historical memory. We need to replenish our family archives with new photos and save them to show to our descendants. Secondly, I wanted to show what impunity does to a criminal. I really want people in Europe to see this project and immerse in our Ukrainian context. It seems to me that these pictures can clearly demonstrate why we are fighting and for what, and that an unpunished criminal will continue to commit crimes again and again.

Can we trust our memory? Can archival photos be a tool for manipulation?

We cannot always rely on our own memory. In psychology, for example, there is such a concept as false memories. That is, a person can be convinced that they remembered everything correctly, but due to certain circumstances, they can have certain gaps in their memory or unconsciously change their memories. That’s why it is important to capture stories in photos. But even photos can be interpreted differently. With all my love for documentaries, I realized that even the most cold-hearted documentation of reality cannot be objective. And yet, I strive to make this project as unbiased as possible. That’s why I accompany each photo with people’s notes, their testimonies.

Commemorative plaques at railway stations in Lithuania. Starting from 1940 until 1952, Lithuanian residents were sent en masse from these places into exile deep into the Soviet Union.

What is the role of the photographer during the war and how do archival photographs of repressed people relate to what is happening now?

A photographer’s role in the war is to document war crimes. This is what photographers like Yevhen Maloletka and Mstyslav Chernov do. Or Yana Kononova, who quite cruelly, but at the same time artistically depicts the process of exhuming the bodies of civilians.

Many stories from the past resonate with what is happening now. Take at least the deportation of Mariupol children to Russia. In addition, we still do not know what is happening in the occupied territories. But looking at the archival photos, I understand one thing.

They tried to destroy us, but they did not succeed, as here they are, the descendants. It seems to me that we are now living in a historical moment. In the first months, I was very worried that Russia would again do what it always does: rewrite history. But I can already see that this time it will not succeed. We are putting a nail in the coffin of the empire. And I would like to finish this project when it finally falls apart.