Halyna Petrosaniak is a poet, writer, and translator from German into Ukrainian. Her first poetry collection Park on the Slope was published in 1996, at the time of the formation of contemporary literature of independent Ukraine. Her poetry is a careful selection of phrases to describe deep, intimate, personal stories. Halyna is the author of such poetry books as Light of the Outskirts (2000), Temptation to Speak (2008), Balloon Flight (2015), Exophony (2019), as well as a collection of short stories Don’t Stop Me From Saving the World (2019). At the end of 2021, her debut novel Villa Anemona was published.

Thanks to her translations, André Kaminski, Soma Morgenstern, Alexander Granach, and Péter Zilahy received their Ukrainian voices and appeared on the bookshelves in stores and private libraries.

For many years, Halyna Petrosaniak has been living in Switzerland, near Basel. Before that, she used to live in Ivano-Frankivsk for many years. This conversation is a portrait dialogue that covers a wide range of topography, memories from the times of youth, and relevant topics of today.

This interview consists of two parts, and here is the first one. [The conversation was recorded on August 17 — ed. note]

Where are you now? Because it’s difficult to guess from your surroundings.

I’m at my place, in Switzerland. This is a house in the village and I’m in one of its rooms, in my office, the bureau, where I usually work. It is close to Basel, 13 kilometers away. However, it is quite distant mentally: the long Jura mountain massif stretches from Basel to Geneva, there are no mountains in Basel itself, but they are very close to it — Basel lies in a valley, and our village is in Jura, on another level.

Today I want to talk about your recently published novel about translations of Rilke’s sonnets, but above all about topography: Switzerland, Ukraine, Ivano-Frankivsk, and mountains.

Let me start with Ivano-Frankivsk. You are not originally from here, but you are connected to this city by many years of living. When did you come here? What was the atmosphere like when you lived in this city?

It was a long time ago. I came to Ivano-Frankivsk when I was a little over 14 years old — it was 1984. I just finished the eighth-year school in Cheremoshna in the Verkhovyna district. After school, there was a question: where to next? We decided that I would go to Ivano-Frankivsk boarding school for the last two years of studies to get my secondary education. There were so-called pedagogical classes. This meant that during their studies students had an opportunity to prepare for admission to the pedagogical institute: twice a month, professors came and had conversations with those willing to enter it. It was a priority for me. And what was also important is that it was a Soviet boarding school with all the benefits — I mean that I didn’t have to pay for education.

So that’s when I came to Ivano-Frankivsk. It was a completely new, strange, incredible world for me, which at first I did not understand at all: where did it all come from, those houses and streets? Why was it so un-Soviet? It struck my eye even then.

I had inner confusion: I could not connect this world of the city with anything I knew before. Those two years in the city, at the boarding school, were very intense, because it was quite far from my home and I rarely went there. So, I stayed and spent the weekends either alone or with someone who had no family and nowhere to return to. In this sense, I’m a rather ‘boarding school’ person. And going back home was also an adventure. I was 14-16 years old, it was far away, and when I left before noon, I arrived home late in the evening, and if it was autumn or winter, it was already dark and scary. I didn’t have a flashlight and had to walk to our house three kilometers from the bus stop through the forest, along a tractor road. Those night arrivals home became an important life experience that tempered me.

And on which street of Ivano-Frankivsk the boarding school was situated?

It is still there, it’s just called differently. At the end of Chornovola Street (back then it was Pushkina Street), I think it was number 130. It was a rather good school, there were good teachers, and the infrastructure was of high quality for the time. I owe a lot to that school. In fact, it was my threshold to city life and to my urban self. This is how my personality has the foundations of rural mentality and soil, and city life: since it started quite early, it is all combined in me.

Later, you entered the faculty of German-Russian philology. When you left Cheremoshna and went to continue your studies at a boarding school, did you realize that you would further acquire a pedagogical education and study other languages?

I realized that it would be pedagogy, but when I entered the university, I didn’t even think of other languages. At school, my German was never particularly good. I showed some interest, because my village school teacher, Olha Petrivna, was a wonderful, knowledgeable and good person who awakened sympathy for this language in me. But I wouldn’t dare to learn German. I did not have and still do not have a special gift for foreign languages (although things are getting better now). I’m not a person who remembers words easily, figures out things quickly or knows how to find a way around — everything took a lot of effort for me. It all happened by accident. When I submitted my documents for admission, I planned to study only Russian philology. I loved both our Russian teacher and the literature of this country, so I wanted to study it. It was back in 1986-1987, it was the Soviet Union, nothing promised its collapse yet, and besides, I didn’t really know what to do at that time. When I handed over the papers, I saw that there was a huge queue of students coming to study Russian philology. And there was another table next to it. A woman sat there accepting documents for Russian-German philology, and there were only two or three applicants. She was bored, and when standing in the first line I approached her, and the lady spoke to me. She asked my name and where I was from. “Oh, are you from Cheremoshna? My classmate teaches Russian language and literature there.” She was referring to my teacher whom I loved very much. Then the woman asked why I was going to Russian philology, as there were so many people, and suggested that I go to her, to Russian-German philology. I refused: “I don’t know German well, I’m afraid and I don’t want to.” But she convinced me that I would learn German from scratch, there was no need to pass an exam or have previous knowledge. And that’s how she persuaded me. It was Alla Tatarenko. I think she still works at the university. It was a fateful incident that fundamentally changed my life. I can only imagine what would have happened if we had passed each other, if Mrs Tatarenko had just left for lunch when I was standing there. But it all happened just like that.

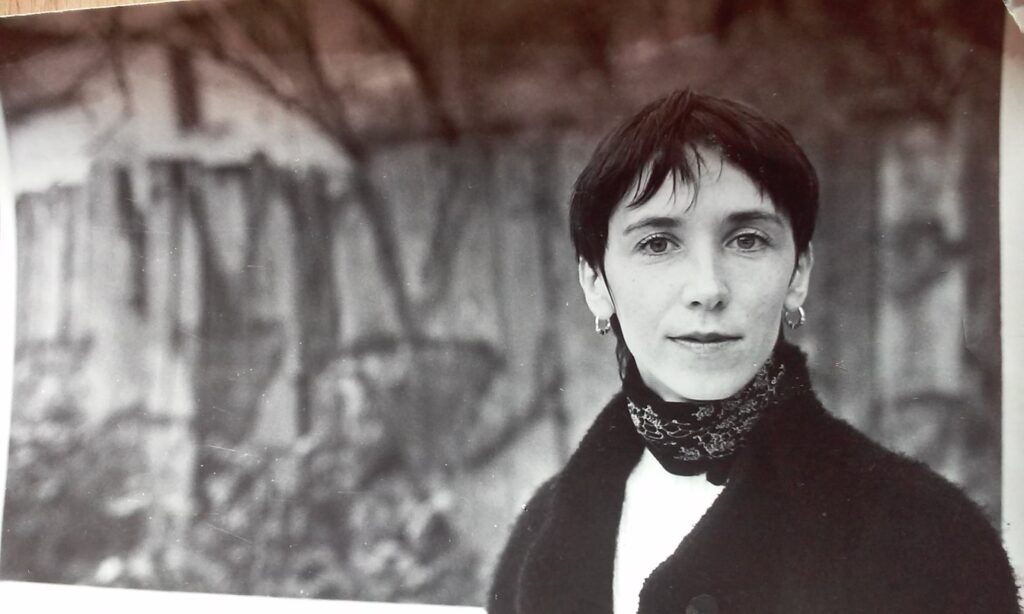

Photo by Taras Yakovyn

In those interviews of yours that I have read over the years, I did not get to hear stories about your parents. And now, when we are talking about childhood, I want to ask you about them. Did your parents support you in what you did? How much parental involvement was there in your life choices?

I grew up without a father — I just never knew him. And unfortunately, we failed to meet: when I started looking for him, it turned out that he had died a few months before. We haven’t met. This also greatly influenced the way I grew up.

My mom did everything she could for me. She is no longer with us. I owe everything to her and my grandmother, who was also not a birth mother to my mom but her stepmother. My mother was orphaned immediately after her birth, her mother died two weeks after giving birth to her. This all happened in the 1940s, during the war, in the Verkhovyna district, in a village on a farm. It was a very hard and poor life. My relatives were peasants who worked hard just to survive. There was no estate, no property, but a modest house, one cow, and a little vegetable garden. It was an existential minimum in the true sense of this phrase.

Therefore, my childhood passed with two women: my mom, a single mother, and my grandmother who was like my true family (she died when I was 20 years old, and all my life then and after that, I considered her my relative). The boarding school was a good option because my trip there was to help my family.

Early in life, when I was 15, my mom once told me: “You’ve made your bed, now lie in it.” She meant: “Everything you do has its consequences, so you have to think about what you’re doing and be vigilant.”

Back then, it did not seem to be something clear and deep, but I kept those words in my mind. Apparently, it worked subconsciously.

When I entered the university or solved some problems in Ivano-Frankivsk, I did it myself, sometimes my friends or acquaintances helped me, but it was all without my mother — she was busy with other things. My brother and sisters were born and there was much for her to do, accordingly, my life was in my hands. Of course, when I came home, she supported me, packed bags with food for me, gave me money, asked how I was doing, saw me off to the bus, and cared for me.

How did your mother react when you said you were a poet?

My mother knew that and encouraged my interest in words. It was she who awakened it in me because she was the first person who read me poems when I was three. Mom loved folk songs and sang a lot when she was young. My earliest memories are of me thinking about a song my mother sings. It was a song about Halia. Not Halia Carries Water, but another, dramatic story where Halia went to the well, fell down and drowned. I was about three years old, and this was my first literary experience: I thought about the song, Halia’s fate and associated myself with her. And that was one of the earliest literary dramas that I experienced.

I remember other cases, in my very early childhood. “I’m a little linden, I’ll grow up bigger, don’t break me!”— I was about three years old when my mom taught me this poem. She also taught me quite a lot of songs that can’t be heard anywhere now. Mom loved poems by Stepan Rudanskyi and some of Ivan Franko’s poetry and knew excerpts from The Painted Fox. This is despite the fact that my mother studied only for five years in the same school where I studied, in the early 1950s, when things were very different. As an orphan, she also had limited opportunities: early in life, when she was around 11-12 years old, my grandfather took her from school and made her look after the children. But my mother remembered a lot of what she learned at school because she loved it all.

Do you remember Ivano-Frankivsk at the time when, in fact, you became a poet and the community around you appeared with which you went through the late 1980s — early 1990s?

Of course, I remember. My interest in literature was strengthened thanks to the literary studio, which I began to attend sometime in 1988. It was headed by late Stepan Pushyk. Everything was valuable there: both the fact that it was Pushyk and those who attended the studio. These are now famous people, such as Mariia Mykytsei, Svitlana Breslavska, Volodymyr Yeshkilev, Oleh Hutsuliak, Ivan Tseperdiuk, Ivan Andrusiak, and Stepan Protsiuk. It was a very favorable environment to be in and I wanted to be a part of it. We exchanged books, there was more to read than in the Soviet times: translations appeared that were impossible before, in particular, in the Vsesvit periodical. We read Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra. There was such a wave when everyone was talking about him. Then there was a wave associated with the Bu-Ba-Bu literary performance group. It turned out that it was possible to write like that, in a hooligan way. That was not my type of literary form, but the fact itself was important: it was possible! All this enriched me and all of us — the living fermentation of everything. A little later, when I was finishing my studies, in 1992, I started working in the same boarding school. They needed people there to work with children during out-of-school hours, do homework together with them, have breakfast, and supervise them. I was a teacher in the first grade and it lasted almost two years, until 1994. At that time, I intensively communicated with my ‘studio mates’, for example, with Volodymyr Yeshkilev. I read much of what he read and found something for myself in it; we were also close friends with Mariia Mykytsei and we read our poems to each other. And then our urban circle became closer, just then it was becoming the Stanislav phenomenon. At that time, Taras Prokhasko finished his studies in Lviv and returned to Ivano-Frankivsk. Izdryk came there, too. Shortly before that, Andrukhovych came back from Moscow. And there was a circle of artists — there was Impreza. And at that time I became a part of this environment: I was not very active, but I always wanted to get closer to it. I remember that sometime in 1991, Anatolii Seliukh came to our institute and told us about the Chetver magazine published by Izdryk and said: “If anyone has good and interesting texts, you can submit them to this magazine.” Those were such historical moments.

Of course, then we followed Chetver and what appeared there. Something was striking for me because I was limited by the framework of art, as I understood it at the time. I didn’t know how to perceive it, especially visions.

But also the texts. I liked a lot of things, but most of all it was about people: Prokhasko, Izdryk, Breslavska, Mykytsei, Andrukhovych, who came to our studio when we studied at the institute and told us that he had a little daughter Sofiika and that he was babysitting her and writing poems in the meantime.

Photo by Yurii Rylchuk

You recall those years with great warmth. And I feel that this warmth has remained to this day. I happened to read an interview where you were the interviewee and Izdryk was the interviewer. And that was an incredibly warm conversation between two people who felt at ease in each other’s presence. Every time I see you performing together with Andrukhovych, I’m amazed by the feeling of warm love between you, and it is very impressive. Which of these people do you keep in touch with and are you still in contact with them?

Not constantly, no. But the inner connection with each of them has never been lost. I sometimes read interviews with Izdryk, Prokhasko or Andrukhovych, and although they are completely different, internally I’m in solidarity with each of them and I understand very well the opinions they express while sharing them in many respects.

On the one hand, it is due to our common past, the way we were formed. On the other hand, everything is relative: unlike me, Andrukhovych was already an established author at that time. This means that I simply took many things from them and made them mine. At the same time, there are other things: the Galician mentality, the genius of the place, and things that go beyond the personal into the wider.

You were the laureate of the Bu-Ba-Bu Award for the best poem of the year. Do you remember what it was like?

Yes, of course, it was unforgettable. It was a prize for the poem Dominican Sisters: “To stay forever in a school of Dominican Sisters near Vienna…”. I wrote it in 1995 in Vienna. The Bu-Ba-Bu Award is serious in one way and in another it is vice versa. Because when it comes to awards, the money equivalent is usually meant, as well as broad recognition by respectable institutions. The Bu-Ba-Bu Academy is very respectable but virtual (it was virtual even before the virtual world appeared).

The prize was arranged in such a way that the one whose poem was liked by two of the three members of the jury during the year, independently of each other, became the laureate. This happened to me in 1996 and it was wonderful. After that, there was a lot of talk about the poem, even the Dominicans wrote to me. I have several funny and interesting stories about that.

As I recall, the award meant that the laureate received a bottle of the most expensive alcohol available at the time. Do you remember what kind of alcohol it was?

It was wine. It seems to me that it was not about all types of alcohol, but about wine in particular. The award ceremony took place in the city library, on Chornovola Street, at the end of May, as part of Andrukhovych’s readings. There were a lot of people: full hall, very festive. Andrukhovych handed me the prize — a bottle of wine. I gladly accepted it, and when I sat down, I held it on my lap in a very light purse. And then Mr. Volodymyr Pushkar came up to me to congratulate me on the award — and he was always a dandy, at that moment he was wearing elegant light-colored pants — I stood up to meet him to shake his hand… And the wine fell out of my bag and the bottle broke.

In the end, everything happened in a very Bu-Ba-Bu way!

I understand that you now write poems in a completely different way than it was when you were young. After all, it cannot be otherwise. Tell us a little about this experience of change: how did you feel this change in creating poetry?

This is a very interesting topic. I think this should be discussed a lot more than it is. They often even condemn a person who has changed. They like to say: “Back then, 20 years ago, you said one thing, and now you say completely different things.” But everything is the opposite: the meaning of life is that we are constantly rewriting something.

Fortunately, as a person who has always respected authorities and was afraid to argue with them, a very timid person, although not so much as to allow myself to be confused, I didn’t get completely disoriented, and I went through my path of development, I didn’t allow myself to be blocked, I got changed.

Intuitively, I felt that literature was my path. Thanks to it, I developed myself, and I think that this experience of mine can be useful for someone else. These personal victories, revelations that I tried to articulate in my poems and prose, my conclusions, even if they are not so important or interesting for the whole world on a full scale, can be valuable, inspiring, helpful for many people, can give an understanding that we are changing, that we can go far in the forest, but reach much further than we thought. This is okay, this is as it should be.

Do you still enjoy writing poetry?

I really like poems. But they are difficult for me to write because I’m used to choosing words thoroughly. Sometimes I have something to say, but then I think: “Oh, it’s so simple, banal, it’s already been said, and in the same words. I’d better keep quiet because everyone already knows that.” And such demanding sometimes blocks me. It’s not something that has appeared just now, it’s been going on for years.

I used to think: it’s too simple, too easy, well, I’m not going to present it to the public now. Everything should be sky-high and very well done.

This high bar was set by those with whom I was friends: Andrukhovych, Izdryk, and Prokhasko. And not only them. The reading experience also influenced my criteria: what is good, worthy or less worthy. Time passes and what I thought of and could write about no longer meets my high criteria, so I don’t write about it.

Photo by Rostyslav Shpuk

You have not been living permanently in the Ukrainian-speaking environment for some time. Do you feel this influence, do you feel that there is a German-speaking environment around you? Does it somehow affect your poetics, your sense of words and what you do in your prose, essays, and poems?

Yes, it influences such things. Although my environment is partly Ukrainian-speaking: I talk to my son in Ukrainian every day. At home, as well as in my head, there are two languages: I speak German with my husband and Ukrainian with my son. Therefore, I am a translator first of all. I must say that both of my languages are imperfect, one gradually displaces the other and they do not coexist in complete harmony. When I get too deep into Ukrainian texts or speak Ukrainian for a long time without reading or writing in German, it is difficult to switch back to German. I make interventions, interweaving Ukrainian syntax with German and making interlanguage mistakes. However, it might be productive: sometimes some of my mistakes later turn into lines of poetry.

You have been living in Switzerland for six years already. Please tell us about your experience of this topographical change: from Ivano-Frankivsk to the Swiss canton. This was an adult relocation. Under what circumstances did you leave and how did you make this decision, how did you settle in Switzerland?

I came to Switzerland when I was 46. I did not plan to start everything from scratch. Then I thought that I’d have better done that, that I had to plan to start life in Switzerland from the beginning. All this now has its positive and negative consequences.

The positive thing is that to a large extent I’m staying in Ivano-Frankivsk, in Ukraine, and this decision is manifested in the fact that I work primarily for my Ukrainian-speaking readers.

I translated books by Soma Morgenstern (the book was published in 2019) and André Kaminski (which has just been published). I wrote essays and poems. I have always been following what is happening in Ukraine — I lived there to a large extent. Especially since my work is at home, at my computer, so I was not very active in contact with the Swiss world. Basically, I still live in Ivano-Frankivsk. Some part of me, of course, also lives here: I try to get to know Switzerland, I travel, I read Swiss writers and get to know their mentality.

In the last 15 years, local history has been very important to me: I worked as a tour guide for German-speaking guests in Ivano-Frankivsk. Involuntarily, I became a bit of a local historian, and this new identity mobilized me: I wanted to tell something about Switzerland to my Ukrainian-speaking readers. I prepared a book of essays on various topics. It will hopefully be published in autumn by the 21-Publishers from Chernivtsi. These are essays written in Switzerland, and they tell about various figures associated with Ukraine, Switzerland, and the countries of Western Europe. For example, Nino Ausländer, the third and last wife of Hermann Hesse, originally from Chernivtsi, who was an interesting person herself. I read her letters to Hesse, her biography, and wrote an essay about her. And there will be many such figures in this book.

You led me smoothly to what I wanted to focus on: the adaptation of different cultural codes. When a person with one cultural experience comes to another country and settles among people with a different experience. I’m interested in the issue of adaptation: what things are different and common between the cultural codes of Eastern and Western Europe, in your opinion?

There are lots of common things, almost everything.

Being here I felt that Ukrainians are Europeans, without any exaggeration. Everything is in common, the only point is in the amount of quantitative practice of this Europeanness.

These values, this way of European life, thinking, behavior of Western Europeans are well known to us, Ukrainians, and we also have them. But if here they are practiced by 95% of citizens, then in Ukraine these are probably 35% — that’s the difference. In Ukraine, we have to work to increase the number of those who implement these values.

I once formulated for myself that in terms of discipline, attitude to work, and correctness in behavior, every Swiss is like every tenth or fifth Ukrainian. Here it is clear that it is simply about quantity, and we have to work on it. I see a space for educational work in this, no matter how strange and retrograde it sounds.

Many people ridicule this position because the Age of Enlightenment is long gone. But no, it has not gone, it is always relevant. And it is important that these values expand and reach the masses.

This is about cultural codes that need to be learned. To use a simple metaphor: you have to learn to use the utensils at the table. Enlightenment is learning. Generally speaking, you just need to learn the etiquette rules in the broadest sense of the term, right?

Yes! You understand why it has advantages, despite all the snobbery. Recently, during the full-scale war, a Swiss journalist prepared an article about the same thing — the difference between Ukrainian and Swiss culture. She asked me to help her. Since there are quite a lot of our refugees in Switzerland, this article was timely for them. She provided several examples: sometimes Swiss families are surprised when they sit down at the table with Ukrainian guests, and Ukrainians do not always follow the etiquette rules: they start eating even before someone says “Bon appetit”. We also generally know that you have to wait for everyone, but not everyone remembers this or is not used to doing this in the family. And why it is necessary to do so is only a matter of explanation.

Main photo by Rostyslav Shpuk