In the spring, Ivano-Frankivsk was overloaded with new people. Among them were the participants of the Working Room residency program, which was initiated by the Kyiv artist and curator Lesia Khomenko. 17 participants from different cities planned to work here for 2 weeks, but stayed for 3 months. The result of that collaborative work was the exhibition, which aimed to find answers to the following questions:

How is our perception of the human body changing?

How does dehumanization work in the context of war?

Is it possible to talk about self-dehumanization or a reflection of propagandistic dehumanization?

What does the ecological aspect of war look like as a gesture of aggression not only by some people against other people, but also by people and non-human actors?

How are memory projects used to justify this war and how are certain events/dates rewritten?

However, in my opinion, the main question, the answer to which artists, curators, and visitors are looking for, is:

who is this exhibition for?

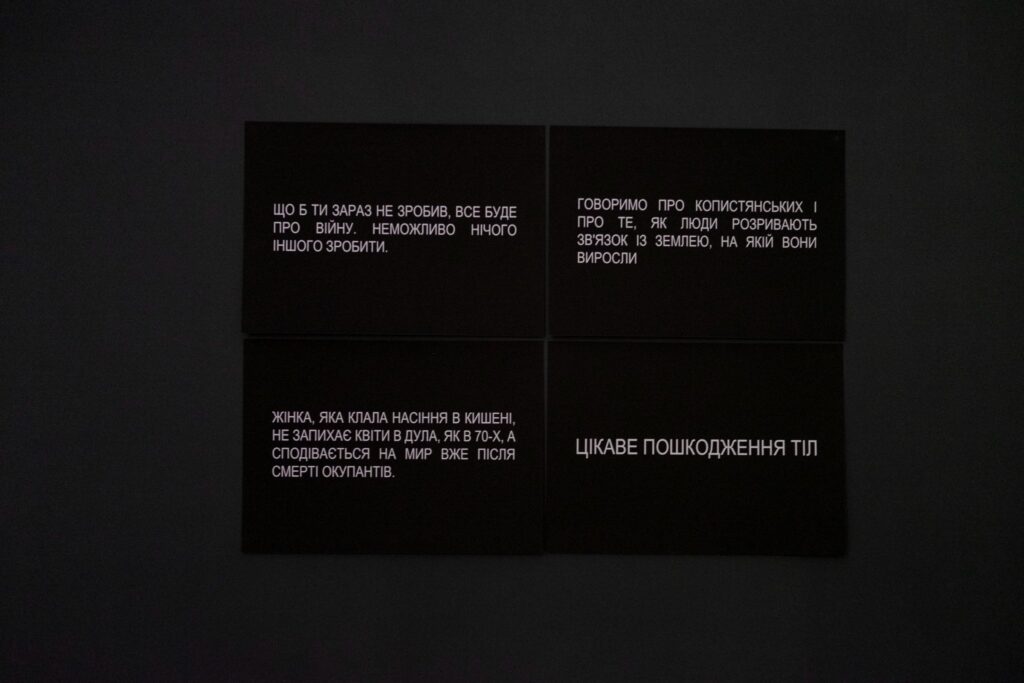

An artist cannot (but) work during the war. “Whatever you do now, everything will be about the war. It is impossible to do anything else,” says one of the quotes, which is also a part of the exhibition (although this particular quote is an excerpt from the discussion of these works, that is, it is not actually a part of the exhibition, but a comment on it).

The Working Room carefully (and detachedly) examines human bodies: bodies in basements, in the ground, bodies alive and not really, enemy bodies and bodies of those we may have known. It peers into the horizon and beyond the horizon. It bakes bread that is impossible to eat and that can only lie as a stone on the soul. It hides behind the two walls. Intently it counts the good news, which is few. It measures the depth of pits from explosions. It sorts out personal belongings. It comes so close to the events that they start to blur in your eyes and you can no longer see anything.

How close should one stand to a painting to actually see it?

How close to the epicenter of the explosion should one be to witness the explosion?

How close should one stand to each other to feel the warmth of someone else’s body?

After all, what is this exhibition for?

Since this exhibition is the result of the residency program, it can be assumed that it is primarily for its creators, being a point of support, reference or destination. Simple and clear work (and for the artist, such work is art) turns out to be an effective practice for (self)preservation in uncertain times. You focus on what you do best and do that job as well and diligently as possible.

Hence, if your task is to experience your personal pain and the pain of other people by turning it into physical objects, you are fulfilling it, no matter how unnecessary it may seem.

We are now in a timeline where we have time to experience the war, reflect on it, and rethink these reflections at the same time. Time inexorably accelerates and times intertwine. The time that passes in the Khata Maisternia space differs from the time that passes through Mykolaiv, Kharkiv, Mariupol, and any city that is under shelling. In this case, the Working Room exhibition becomes a kind of time capsule: these are not just works created about the war during the war, but works created in the particular spring of the war. When the skin was still more sensitive to pain, and the mind — to the news. When death was still news and not a painful inevitable routine.

So, who is this exhibition for?

The memory will fade out. With each passing day, week or month of the full-scale war, it can be more and more difficult to recall each of the events in detail: the movement of armies, shelling, houses, malls, railway stations, basements, sirens, hits, explosions, medical tourniquets, the taste of blood, dirt, fire, and lack of sleep merge into a single stream, in the middle of which particular implemented creative projects remain as islands.

One of the tasks of art during the war is to prevent our memory from falling into oblivion (something it relentlessly desires to do in order to preserve itself). Art visualizes memory, captures, and records it on canvases or photographs.

This exhibition is a room where our belongings are stored and which we don’t really want to return to. But we know the way, we can always return, when we feel we need to.

I’m grateful to Sasha Kurmaz, Kateryna Aliinyk, Taira Umarova, Yaroslav Khomenko, Yevhenii Arlov, Nikita Kadan, Maria Leonenko, Yevhen Samborskyi, Leo Trotsenko, Olia Yeremieieva, Yarema Malashchuk, Oleksandr Surovtsov, Daniil Halkin, Lesia Khomenko, Zhanna Kadyrova, and Kateryna Buchatska for articulating these questions (and answers).

Main photo by Oleksandra Soloviova. Photos by Taras Telishchak