How come the space of our memory is the space of war? Natalia Derevianko, a historian and artist, tells about how the Russian-Ukrainian war reopened the wound of Ukrainian society’s memory, about artistic commemorative acts and key points since 2014, and about contemporary artistic practices as a method of existential documentation of war reality.

no pasaran!—a digression into the history of impossible memory

On the night of February 23-24, 2014, unknown artists painted part of the sculptural composition of the monument to the Soviet Army in the city of Sofia in yellow and blue colors, thus expressing solidarity with the Ukrainian Maidan Revolution and undermining the Soviet dogmatic black-and-white tradition of commemorating World War II. At the same time, knowingly or unknowingly, the unknown activists restored certain historical justice, because, on September 8, 1944, it was the troops of the Third Ukrainian Front that launched an offensive on the territory of Bulgaria, an ally of Hitler’s Germany during World War II.

The tradition of public interventions in the space of this monument was started by the anonymous Bulgarian art group Destructive Creation in 2011. It was the In Step With The Times campaign, when artists painted the sculptured Soviet heroes turning them into American superheroes. In 2013, the monument to the Soviet Army served as a canvas for two more anonymous political statements by unknown activists.

Photo by Destructive-Creation

In August, the monument was covered with pink paint and signed “Bulgaria apologizes”. It was a gesture of solidarity with the Bulgarian government, which in March 2013 first apologized for the deportation of 11,000 Jews during World War II. And in the summer of 2013, the sculpture of the Third Ukrainian Front was used to make another gesture—a gesture of solidarity and support for the Russian punk band Pussy Riot. In 2014, the memorial also became a place for public expression of condemnation of the annexation of the Crimean peninsula. In fact, if you search for “Sofia Red Army Monument” in the Google image search engine, you can find a lot of interesting facts.

One might say that in Ukraine, as in the rest of the countries of the former socialist bloc, the possibility of grassroots unofficial commemorative practices appeared after the collapse of the Soviet Union. But that would not be true.

In the 1990s, the freedom of public gestures related to memorial culture was very limited. Here is a random poetic reference (found at the Kyiv flea market by accident)—an excerpt from a 1998 poem by Mykola Som, a poet of the sixties, titled To the Immortal Lenin:

It’s time to bury him—he stood a lot like hell,

But our village council guards him well.

They tie a dog to him at night.

Armed with the method of symbolic & interpretive anthropology of Clifford Geertz, we can say that such a cinematic scene with a guard dog tied to the monument of the Soviet founder was both rather comical and nevertheless an extremely normal phenomenon during the early years of Ukraine’s independence. That is, the 1990s can be defined as a period of Platonic memory wars: one could talk, think, and look, but not touch. But this, of course, is about central and eastern Ukraine.

The first wave of anti-October demolitions swept through Western Ukrainian cities in 1990-1991. In Ivano-Frankivsk, they said farewell to three-stories-tall Lenin standing in Franko’s place on October 9, 1990. By the way, in 2008, The Ukrainian National Idea, a book by Myroslav Davydiv was published with the funds received from the sale of the copper in which the concrete sculpture of the leader was “dressed”. Today, Ivano-Frankivsk literary figures still follow the tradition of cultural upcycling: the Drunken Boat publishing house published their first book, The Unfinished Crusade by Rafał Wojaczek, with the funds from the sale of a bonistic rarity of the early years of Ukraine’s independence—a defective 50 hryvnia banknote.

Lenin in Ivano-Frankivsk

In the central part of Ukraine, drastic wars against monuments to the October Revolution began in the 2000s, but even back then this trend was rather isolated exceptions—until the Maidan Revolution. The real boom of Leninfall in late February and early March 2014 began on December 8, 2013, with the demolition of Lenin in Kyiv.

Some could not believe that it really happened, and some were shocked that for so many years the monument to Lenin stood on the central boulevard of Ukraine’s capital. Even more surprising was how many Lenins were found in the cities, towns, and villages of independent Ukraine. This symbolic and resonant event turned out to be the Rubicon for political consciousness, after which a number of transformational processes were launched in various spheres of Ukrainian culture.

It is also worth mentioning that before the demolition of Lenin in the capital, there was still public condemnation of the Soviet memorial heritage/nationalistic new memorial buildings (for example, 46 monuments to Stepan Bandera were erected during 1991-2013). It was a crude subcultural war based on historical hatred between communists and nationalists, which included real street «battles for monuments»: knocking off the nose of the leader of the proletariat, returning the nose to the leader of the proletariat, desecration of graves of OUN members and monuments to nationalist leaders, beheading and restoring the head of the monument to Stalin in Zaporizhzhia in 2010-2011, frying scrambled eggs on the Eternal flame monument in Kyiv in 2010, etc. This aggravation was provoked by Viktor Yushchenko’s Decree of 2007 on «Dismantling monuments and memorial signs dedicated to figures involved in organization and implementation of the Holodomor of 1932-1933 in Ukraine and political repressions.»

Therefore, since independence, in Ukraine, several irritating suffocating loops of memory have been formed, which are related to the Soviet past (the figure of Vladimir Lenin, the October Revolution, World War II) and the inability of the political elite to assimilate and facilitate it. And it was the Maidan “farewell act” to Lenin and the “decommunization package of reforms” of 2015 that released the artistic imperative into the space of grassroots commemorations, which enabled the multi-voiced public artistic political gestures and statements, and eventually opened the field for not-so-much-denial-as-understanding of the controversial past and working out historical identities and attention to cultural heritage.

Except for the fact that the war started, which is still going on.

hard memory as a rethinking of symbolic space

If monuments could talk, they would tell us a lot about our past: about revolutions, upheavals, people at mass demonstrations, and wars. Silent witnesses of big and small events on the streets of cities and villages, they are our liaison between history and the present.

However, it is not they, but we who talk to them.

In the autumn of 2015, the work team of the Presmash plant in Odesa asked the local artist Oleksandr Milov to transform the Lenin monument into Darth Vader. This is how the workers reactively saved their symbolic space from the decommunization guillotine. A boom in grassroots, mostly yellow and blue, reincarnations of Soviet characters and symbols took place all over Ukraine, which was studied and is being studied by the Kyiv cultural heritage preservation formation DE NE DE.

In Kyiv, a two-year commemorative performance in several acts took place on the empty pedestal where the leader of the proletariat used to stand (until a metal trident finally took his place).

In the summer of 2016, a group of artists carried out the ascension of the Holy Mother of God from a paperweight onto a pedestal. Cheerful paper garden gnomes were placed at the foot of the colorful paper Virgin Mary. Such an artistic statement of the artists regarding the de-occupied commemorative space of the metropolis was also a proposal to cross the dimension of the political, which makes the understanding between people throughout the whole country so difficult, and to turn to the cultural coefficients of Ukrainian identity.

Virgin Mary with gnomes (from the artists’ archive)

Unfortunately, the Mother of God fell on her face due to a strong gust of wind a few hours after the ascension.

Next, the mission of reinterpreting the undefined desolation of memory on Tarasa Shevchenka Boulevard was undertaken by the IZOLYATSIA Foundation, which had just then been evacuated from Donetsk temporarily occupied by Russians. During 2016-2017, as part of the Social Contract project, they held four international competitions for four ideas for temporary artistic interventions at the site of the former Lenin monument:

1. The method of subversive affirmation, Inhabiting Shadows.

Cynthia Gutiérrez, a Mexican artist, invited all interested to stand on the site of the monument to inhabit the «shadow» of the past. Above the pedestal, she built scaffolding in the form of stairs, allowing to climb the monument from both sides.

2. Commentary on the pillarized regime of memory, Endless Celebration.

Mahmoud Bakhshi, an Iranian artist, installed a light neon installation on the pedestal: a kind of traffic light, where red is the silhouette of Lenin, yellow is the pop singer Madonna, and green is the Virgin Mary.

Although the figures themselves are symbolically distant from the Ukrainian context, from the point of view of the theory and practice of memory, the form of public commemoration of different interpretations of the past, which takes into account competing visions of history, is a rather progressive tool of memory politics*. And for Ukraine, which, on the one hand, is too consolidated and, on the other hand, is divided by the full-scale war, it can also be helpful.

*It is the pillarized regime of memory (a category of the theory of the politics of memory by Jan Kubik and Michael Bernhard) that was taken as the basis for the reformation of memory politics in Spain. This was very timely because post-Franco Spain inherited a divided memory of the past: Spaniards (like Ukrainians) fought against each other during the Civil War (1936-1939), and until 1975, when Franco died, only one historical narrative and, accordingly, one historical identity, was the only one acceptable. Ukraine also inherited a similar trap of historical memory, the divided memory of Ukrainians who fought against each other as part of the Red Army, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army. Read more about the «Spanish scenario» for resolving the memorial conflict.

3. Post-humanistic approach vs pacto del olvido, Ritual of Self-Nature.

Isa Carrillo, a Mexican artist, proposed to solve the problem of commemoration at the site of the demolished Lenin monument by ‘taking over’ the monument with living plants. The artist covered the empty pedestal with living plants: rosemary, mint, etc. On the one hand, their task was to mask the stone column, while on the other hand, to “purify” the site that was associated not only with the Soviet leader but also with a gallows that was placed there during the Nazi occupation.

On the one hand, such a gesture can be perceived as a pact of forgetting: to let the plants occupy the remnants of memory. But on the other hand, caring for nature in times (and about times) of tectonic shifts in history is also an act of commemoration. In the spring of 2022, in the village of Kukhari (Kyiv Polissia) liberated from the Russian occupiers, local arborists healed a 350-year-old oak tree that was damaged by an explosion and saved a Ukrainian soldier with its trunk. Such practical commemoration is, in fact, a local memorial of today’s war.

4. Participatory performative method, A Monument for Kyiv.

The final act of the IZOLYATSIA’s project is a performance by Romanian artist Manuel Pelmuş: a proposal to look at the place of freed memory as a space for collective experimentation. Involving the locals, the artist staged a choreographed action of subversive and affirmative yoga around an empty pedestal: by standing like Lenin, the participants of the action with their own bodies were creating a new monument that they would like to see in the city square.

A similar epic happened in 2017 with the horse of the Mykola Shchors monument standing in Kyiv. In March, concerned citizens sawed off and stole his right foreleg. In April, artists (those who elevated the Virgin Mary to Lenin’s site) staged an artistic intervention at the site of the so-called Shchors in a Cube monument. On the four sides of the blue-yellow cube that surrounded the Shchors statue, the artists hung four banners featuring Count Bobrynskyi, Symon Petliura, Hetman Skoropadskyi, and Nestor Makhno. Each of the characters held a stolen horse’s leg in his hands, symbolizing «the price for the place of a fallen commander». Such a critical gesture takes the probable attempts to build a new historical narrative simply by replacing some personalities with others to an absurd level. But at the same time, it shows the multiplicity of perspectives and gives space for the voices of mnemonic pluralists (after all, the mentioned historical characters were chosen by the citizens who are concerned about historical memory). And in the autumn, a group of unknown artists from Kyiv restored a bronze horse’s leg made of plaster (the Step public action) by tying it with a yellow-blue ribbon to the horse’s body. In 2022, the anonymous art collective Decision-Making Center in the microfilm Madcap actualized the presence of a monument to the Red Army commander in the capital of independent Ukraine during the full-scale war against the vestiges of the Soviet Union.

Shchors in a Cube. Photo by Mitec

In 2019, another action to reinterpret the Soviet military monumental heritage against the background of Russia’s war against Ukraine stirred up the air quietly. Members of the radical art collective Warriors of Good and Light set fire to a tank monument in Chernihiv with the help of Molotov cocktails. With their gesture, the artists declared the unacceptability of commemorating the victory of the Soviet Union during the ongoing war of Russia (which considers itself the heir of the USSR) against Ukraine and the inconsistency and duplicity of the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance. For this, they were charged with 4,5 years of imprisonment. The artists are still under a suspended sentence.

The Chernihiv tank (from the artists’ archive)

Perhaps, if Russia had not launched the full-scale invasion on February 24, 2022, Ukrainians would have continued to commemorate the Soviet Union’s military victories.

For me, it was important to capture (perhaps for the last time?) the date of the «great victory» in Troieshchyna (in the residential area where I spent my childhood and where I immediately returned to from Nadvirna, once the full-scale invasion began), as well as to personally join these celebrations.

So on May 9, 2022, having collected the commemorative props, we came to the obelisk in Desnianskyi Park near the Florentsia cinema. It was 7 o’clock in the morning, and a small group of elderly people with red carnations had already gathered around the monument. Surprisingly, no one stopped us from putting a giant bubble condom on the 9-meter obelisk: I guess because of our reflective orange vests. And some early risers even asked us if we needed any help. Amazingly, the laying of flowers and candles continued even around the condom-covered organ of Soviet memory.

soft memory as a reset of the identity space

Together with the reinterpretation of the symbolic space, alternative commemorative practices also began to take on more institutional forms. In 2016, the Ukrainian Institute of Scientific and Technical Expertise and Information (Plate building on the Lybidska Square) hosted the DE NE DE exhibition with more than 30 artists from different cities of Ukraine participating—it was the result of the «Upon Boh» residency in Vinnytsia and subsequent expeditions to Sloviansk, Sievierodonetsk, and Mariupol. Also, it was a kind of response to the «decommunization laws» of 2015, which made visible the need for revision and objectification of historical processes in Ukraine.

In 2019, in Mariupol, close to the front line, an interesting collaboration took place between the TIU Platform and the Mariupol Local History Museum, which resulted in the experimental museum project titled Decom.Propaganda. The exhibition was devoted to the problem of the monopolization of national memory (processes of decommunization) and challenged the limited understanding of heritage as a tool of political struggle/security. Instead of the usual precautionary information stands reading: «Do not touch!», at the entrance to the exhibition, visitors were greeted by a red banner with classical symbols and a call to unite, under which there was a sign: «Comrades! Be careful! Objects of history and art can be offensive!»

Mariupol, the Decom.Propaganda exhibition. Photo by Natalia Derevianko

Similar collaborations between contemporary visual artists and state museums took place also in other Ukrainian cities, such as Lysychansk, Kmytiv, and Stanytsia Luhanska. In the latter museum, in 2018, at the exhibition titled A Spinning Wheel, A Saber, and A Deer, it was probably the first attempt by contemporary artists and local museum workers to comprehend the Russian-Ukrainian war (the building of the Stanytsia Luhanska Museum itself was scarred by shelling back in 2014).

Stanytsia Luhanska. Photo by Mykola Ridnyi, Prostory

The full-scale Russian invasion brought the front line closer to each Ukrainian city on the existential level, which even being «rear» bears the traces of wartime in the form of checkpoints, anti-tank hedgehogs, sandbags, and monuments enclosed in cubes.

In the fall of 2022, in the center of Ivano-Frankivsk, the Alley of Glory in memory of the fallen defenders since 2014 began to be created. Cubic frames were placed on the central pedestrian street, on which banners with the faces of the fallen heroes and heroines of the Russian-Ukrainian war were hung. And the very program of the City Council «Ivano-Frankivsk — the city of heroes», within which the renewal of the Alley took place while manifesting the mission of popularizing knowledge «about Ukrainian heroes who lived or worked in the city», brought together figures of the 19th century and fighters of the ATO and AFU on its website, artificially condensing the historical narrative of the last two centuries. Also, once a month at 9 a.m., one can hear a Memorial Bell for fallen soldiers (the opening of the Memorial Bell, by the way, took place on January 1, 2022—two months before the full-scale war).

Generally, the official practices of commemorating today’s war initiated by the administrations of cities, villages, and even individual institutions, have continued since its very beginning. As early as in 2014, schools and museums began to create «ATO corners» with artifacts and stories of fallen soldiers, as well as memorials or alleys of fame with photos of fallen fighters. This form of commemoration, although quite spontaneous, has already become traditional and classic, as well as more accessible to a wider community than niche artistic initiatives.

However paradoxically, two models of public commemorative practices of the war actively coexist in Ivano-Frankivsk. While administrative commemorative practices fulfill the task of basic remembrance, the art projects are more reflective.

In the past few years of the war, in their work, Ukrainian cultural figures and artists have increasingly turned to personal, family cultural memory, guided by an individual-group approach to history. This could be defined as software memory since it appeals to deeper foundations and fills not so much and not only the lacunae of memory but also of identity. For example, in 2018, the Carpathian Cult ethnographic DIY project was launched in Nadvirna, the Ivano-Frankivsk region. Its founder, Khrystyna Bunii, creates a certain visual cultural and anthropological anthology of the Carpathians from artifacts she finds on expeditions to the villages of the Ivano-Frankivsk region and local private museums, libraries, and archives.

It is this model of memory, horizontally formed and focused on microhistory, that is very useful both for resolving conflicts related to the past and for introducing new forms of commemoration related to the ongoing war.

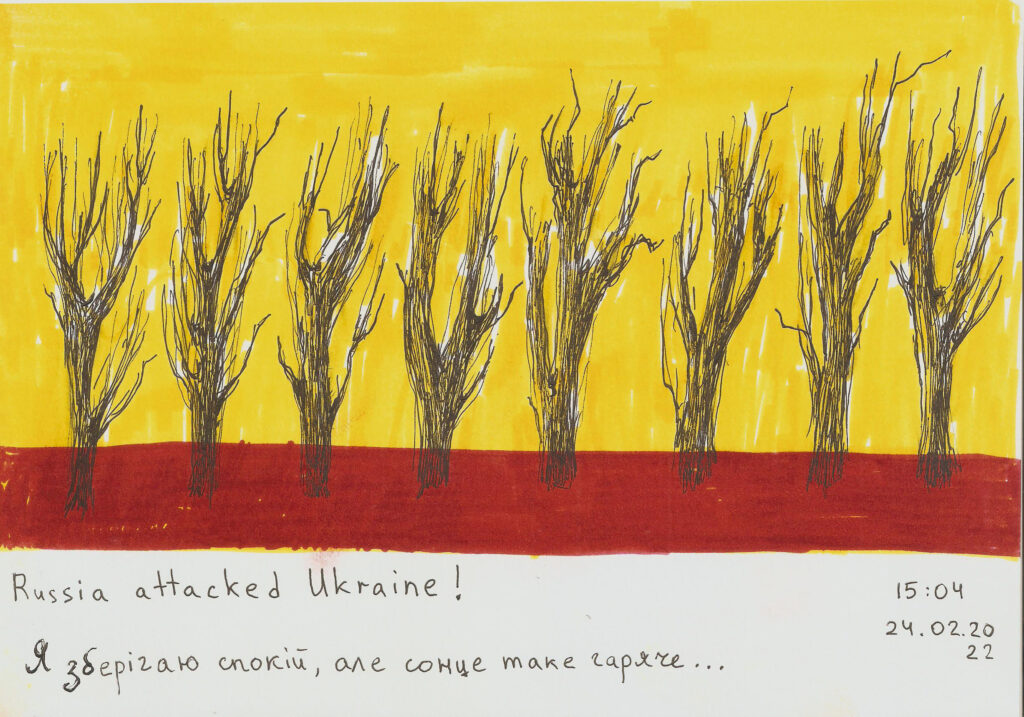

Since February 24, 2022, the process of capturing the war in Ukrainian art has become more intense than ever. In the first month of the full-scale Russian invasion, Lviv artist Yurii Ivantsyk created about a hundred sketch paintings titled Russia Attacks Ukraine!—a certain chronicle of news recording tragic and heroic events from all over Ukraine. Artists’ diaries, either more personal or less subjective, are an extremely important source of documentation, especially when it comes to the first extremely anxious months of the war. As early as in late 2022, a series of publications and anthologies of the first months of the war, recorded in the works of artists (the third issue of the Luhansk magazine +/- Infinity, the second issue of the catalog of the Lysychansk Nevidderesh Gallery, etc.) was published in Ukraine.

Yurii Ivantsyk, from the Russia Attacks Ukraine! series. З архіву художника

The conditionally safe city of Ivano-Frankivsk became a kind of cultural refuge—both for artists who evacuated from occupied or destroyed cities and villages and for artistic events. In March, in the studio of VEZHA TV and Radio Company, for the first time, musicians Illia Razumeiko and Roman Grygoriv who relocated from Kyiv played the 7-hour play Mariupol, which was created two days before the full-scale war began. On the same day, a Russian plane dropped an aerial bomb on the Mariupol Drama Theater.

«How shall we remember this war?» is perhaps a bit hasty, but no less relevant and important question, which is not out of place to start thinking about now. Shall we remember the cold death of exotic heroes in the Hryshko Botanical Garden in Kyiv? Shall we remember the heroism of the Irpin River, which helped save the capital from occupation? Shall we remember that it is Ukrainian fighter jets that are flying over Ivano-Frankivsk?

One of the topics of the recent exhibition at the Asortymentna Kimnata gallery titled Behind the Tree is a Tree was the commemoration of the war. The perspective and experience of the war of artists from different cities across Ukraine, civilian and military, formed the basis of the exhibition created as part of the art residency in the village of Babyn, Ivano-Frankivsk region, «When was the story interrupted?». Trees are destroyed by the war. Trees are protecting Ukrainian soldiers in the Luhansk region. The Carpathian Mountains, which have become a temporary shelter for those who have no home anymore. Fragments of missiles and projectiles found on the streets of the home city. The scenery is like a landscape of the memory of generations.

The artwork by Three Practices of Realism

***

War optics is the most sensitive to memory. War renews the lens through which we look at our past. A theoretical look at history is overgrown with empirical connections with the present; we empathize because we feel historical events in a completely different way, one might say—as a personal physical experience.

Since the beginning of the full-scale war, social practices of commemorating and/or processing the past have multiplied qualitatively and quantitatively. On the Day of Remembrance of the Babyn Yar Tragedy, September 29, 2022, Chief Rabbi of Ukraine Moshe Reuven Azman blessed the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of Ukraine Valerii Zaluzhnyi and the Ukrainian military for victory. It is hard to imagine such a deep inclusion of the state in the memory of the victims of the Holocaust at any other time (although it should not be forgotten that the concept of memorializing Babyn Yar has not yet been considered either in the Cabinet of Ministers or in the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine).

But even at the grassroots level, at some distance from the front line, history becomes a certain support, sets the framework for (re)interpretation, and ultimately helps to see and define the banality of evil. In addition to the new practices associated with today’s war commemoration, the commemoration of the past (wars, famines, genocides, and repressions) is at the same time a mold of our memory of ongoing war.