I suffer from hayfever, so I wasn’t able to enter Kurgans, Tombs and Us by Oksana Pohrebnnyk, Zhenya Milyukos, and Anna Ivchenko. I kneel at the burlap yurt’s threshold. A pungent, warm atmosphere emanates from two hay bales on the ground inside, positioned intimately like benches in front of three screens that alternately display wintry landscapes — trips to a kurgan (an ancient burial mound), apparently — and snippets of white sans serif texts on a black background. In one extended video segment, tattooed hands spread white gauze on the frosty clotted soil of an agricultural field. The gesture touches a pre-memory suggestion of burial. Because I can’t fully immerse myself inside this work, I find myself kneeling among it and other works, inside the curators’ spatial arrangement of disparate ideas that form a whole. To my left, out of the corner of my eye, a small concrete stela by Marta Dyachenko balances brutally. In the corner of my right eye, the pink and blue triangles of Sasa Tatic’s Flow look shrill and sickly. And behind my ears, the sound of Pavlo Kovach swabbing blood off the inside of a military truck reverberates hollowly.

I’m surrounded. I can’t enter the yurt, I can’t touch the soil, I can’t breathe the air, and I can’t shelter myself from hearing the scrape of the scrub brush, dark and sticky with human fluids.

This is a calculated arrangement, and I consider that even though my allergy to the inside of the yurt is particular to me, it feels right to be on my knees in this space.

Photo by Karl Aner

where it all goes is dense. Not claustrophobic, not overwrought—but thick, heavy, syrupy, weighted down with an even pressure, like a funeral shroud held in place by memory objects. Ukrainian artists are paired with German artists in the second iteration of a curatorial project by Alyona Karavai and Benjamin Gruner. The first exhibition, what we are made of (which I did not visit) was in Chemnitz in May 2025. The exhibition text here explains that some of the works on display at Asortimentna Kimnata are new, shown for the first time in this exhibition, while some were produced for the German iteration, and still others pre-existed the exhibition series. This backstory helps. The exhibition feels like it is in multiple places at once, which may explain the title. In the exhibition guide, the title is printed both with and without a question mark. Both make sense, but for me the show itself feels like something of an answer, and not a hopeful one. It is as if someone is waving their hand vaguely in some direction, without looking, resigned to a future with which no one is pleased. It’s not about dread, it’s about inevitable processes, and a common acknowledgement of what we must endure.

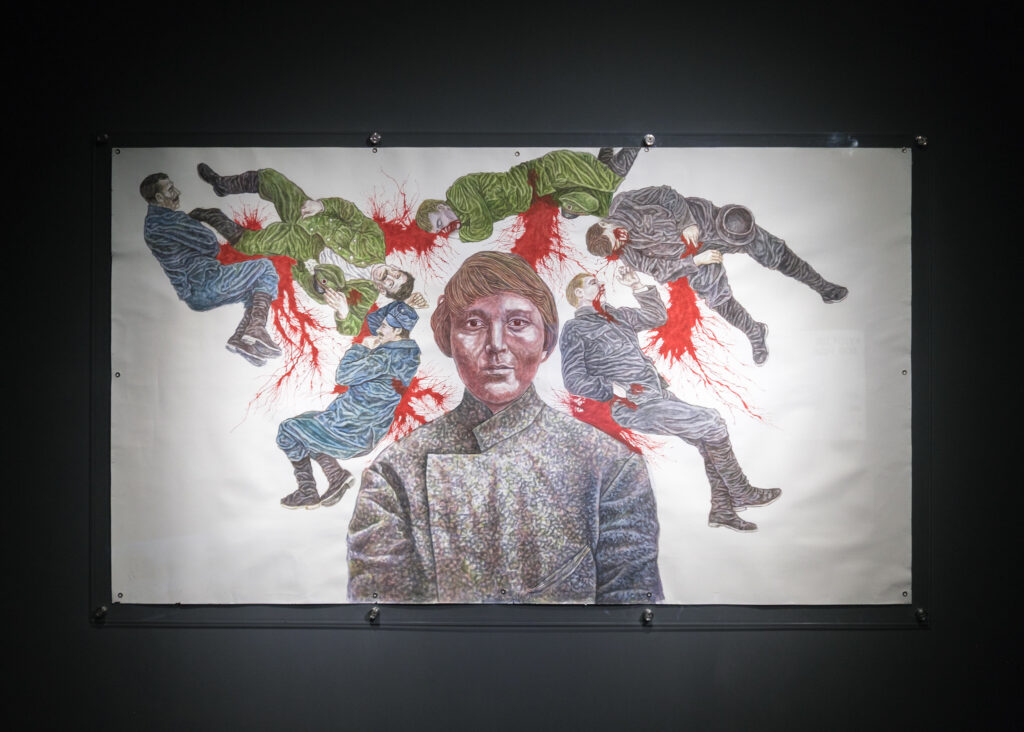

I started with Kurgans, Tombs and Us because it made me physically feel the whole of the exhibition. However, if we assume the exhibition wall text is the start of the narrative, this piece is in the second half of the show, and we should start at the beginning. The first room, with dark grey walls and low light, contains only two works. Across from the wall text we are confronted with Maria, a large-scale watercolor painting by the late anarchist artist Davyd Chychkan, from his During the War series. The war in question is not the current Russo-Ukrainian War, however, even though it was already two years into its proto-form when the work was made in 2016. The drawing depicts the large face of a woman, Maria, gazing at us from in front of a composite bloodbath— World War I anarchists, executed variously and brought together here by the artist. As with so much in this exhibition, the image’s background context is chilling. Chychkan was killed just two months ago on the front line. While he was a frequent fixture in exhibitions previously, his presence seems more essential now. This follows a tragic script—the rush to show Marharyta Polovinko’s works after her death last spring, the ubiquity of Artur Snytkus’s face in Kyiv’s art spaces—each posthumous celebration of an artist and their impact on their community is notable and powerful. It is right to honor the dead, it is right to praise the heroes whose lost lives allow this gallery to still stand. What better place to hang their works?

Photo by Karl Aner

The feelings evoked by the works of fallen artists are complex—the positionality of the viewer (me), the positionality of the curators, our right to their work, our right to add our own layers to their work. Am I looking now at the works, or am I looking at the paradigm of struggle that transforms flesh and blood humans into martyrs? I am told by the curators that conversations about the inclusion of Chychkan’s work predated the artist’s death, but does that change the implications? The gore and history of Maria makes me think that artists with a defining ideology, like Chychkan, transcend more effortlessly into this symbolic state, posthumously crystalized, so maybe the martyrdom is natural in some way. Artists whose lives present more ideological ambiguity, like Polovinko, are being ascribed new posthumous readings. I don’t know which is good or bad, I just observe it, and know that the hanging of this picture now, in this gallery, is part of it.

I don’t know by sight the bloodied faces in Chychkan’s drawing, heaped together with the artist’s characteristically meticulous line work seeping bloody towards the edges, towards the viewer. I try to stop myself, but I see Davyd among them now, the only face I would know in that heap. I wonder if I would recognize him, if I came across his body in such a state. I would not expect him to recognize me if our roles were reversed. But I immediately reproach myself for the narcissism of that thought.

He died for his country and ideology, both things I still can’t touch as a foreigner, no matter how close I tell myself I come to it by living in Ukraine. Involuntarily imagining myself in such a heap emphasizes my own distance from his loss, the sacrifice that now makes his face known, symbolic, iconic.

I never knew him as a hero, but now I see that that was not because of him, it was the fault of my imagination. I only knew a thin guy who liked drawing, whose hand I shook here and there at apartment exhibitions or mutual friends’ back yards, places as far from the battlefield as I can imagine—until I consider the actual battlefield. It has always been in someone’s apartment, or in someone’s friend’s back yard, just not mine. As I work through this personal reflection, Chychkan’s painting seems like a focused spotlight. I see myself not with the heaped dead, but lumped together with all the tepid allies of Ukraine, with our anaemic NIMBY ethics and promises.

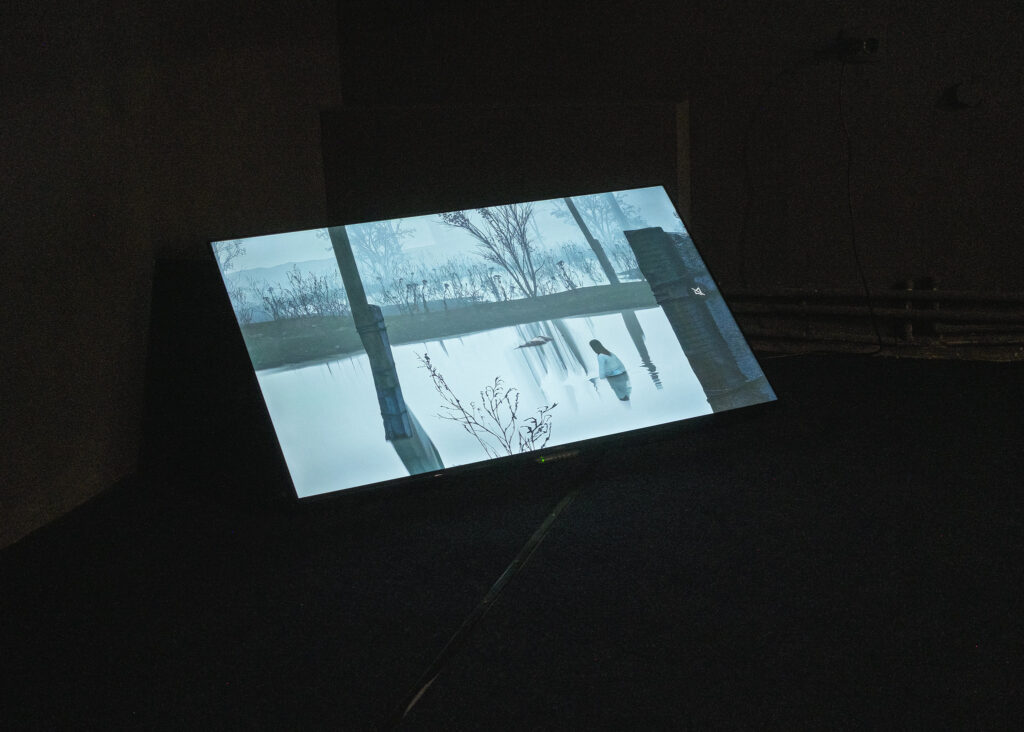

Facing Chychkan’s Maria, is Katya Buchatska’s video Water Proof. The work is a suffocating emotional trap disguised as a trailer for a videogame. The faux-game’s protagonist, a pregnant woman, spends most of her time facing away from us (and away from Maria). It feels like she is hiding her face, but if she is, it is an emotion beyond shame. This may be less of an artistic choice and more a quirk of the form—the dynamics of a first person open world video game—but her occulted bodily orientation closes whatever gulf there might be between shame and the unglamorous business of survival. In Water Proof, we find that the two are not so distant, just like facial expressions of agony and ecstacy.

Photo by Karl Aner

The protagonist searches for her lost dog Sirko in a flooded and desolate world. The landscape is mined, suggesting that we are witnessing the aftermath of war. Even though the danger presented by the mines seem to factor into the plot, the suffocation of the video is internal, expressed by three constantly refreshing status bars representing thirst, the need to urinate, and the need to relieve stress (achieved through crying). This pressure, and the sodden ground of the world, seem, like the blood of Chychkan’s painting, to seep out of the edges of the frame, and fill the gallery.

The adjoining room further unfolds the offscreen edges of Buchatska’s world into a John Carpenter-esque sci-fi dystopia. Theresa Rothe’s meek looking Humanpigdog could certainly be a mutant from a b-movie sequel to the game. The beast does both horrible and cute well, and its endearing hideousness makes me wonder if perhaps this is “Sirkoooo!”, the lost dog that Buchatska’s protagonist is still calling to from the other room. Many things here are both palatable and toxic. I wonder how this animal would smell, in its untaxidermied form—heavy, musky, and wet. The curatorial description tells us that in Ukraine “pigdog” is a derogatory term for russians. For my part, I’m not sure that verbal coincidence has much bearing on how this sculpture takes up space in the room. The beast seems unfortunate more than malevolent, a victim rather than a perpetrator. Looking into its eyes (as the exhibition guide recommends), I do not think this creature appeared here as part of a vengeful campaign of polluted history and lethal cynicism. Its uneasy form strikes me as a product of such circumstances, not an agent. This doesn’t mean, of course, that the animal doesn’t bite. It simply means that there is a place for it in this room, and if it were a russian humanpigdog I can hardly imagine viewers sympathetically accepting its presence.

Photo by Karl Aner

Nearby is Poor You by Elke Biesendorfer, a glazed ceramic baby spoon covered with spikes. Just as I can’t help but see Sirko as the Humanpigdog, I can’t help but worry that this will be the only feeding implement available to Buchatska’s protagonist when she finally gives birth. Grouped with Buchatska, the spoon becomes another comment on birth, childhood, future generations, or, the future more broadly. While this might have a different meaning in, for example, a show about nostalgia for our own childhoods’ in the past, here the childishness asks: what is the world these children will be born into, and what is the future world in which they will grow into adulthood? For this exhibition, that future feels decidedly dark. But, maybe this is also an image of adaptation, of plenty—this warped spoon might be appropriate for the mutant mouths of the children of that dystopia.

Photo by Karl Aner

Fabian Knecht’s Brown Cable is all about making an invisible threat visible. A cut white power cable dangling from a wall socket is stripped back to reveal (presumably live) copper wires and their brown and blue sheathing. I didn’t want to test the 220 volts by touching it, but I also don’t need to to appreciate the suggestion of threat. The text explains that these are the colors of the far right political party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD). The metaphorical suggestion is that these colors and the danger of their voltage are under the surface of everyday life (at least in Europe). The point is well taken, especially considering the persistent debate about European energy dependency on russia, which effectively funds the russian war machine to keep the continent warm. There are of course many alleged links between the AfD and the Kremlin, as with most destabilizing fascist movements in Europe.

The piece works as a kind of diptych with Mandy Knospe’s 27/08/18, a set of three a4 prints on the side wall, or at least the works offer each other mutual thematic support. Here the rightwing drift of the European political landscape is visualized in patterned digital collages using source images of anti-immigrant demonstrations in Chemnitz in 2018. Like in Chychkan’s work, the period addressed is already historical, but also uncomfortably contemporary. The 2018 event was no doubt part of the broader anxiety produced by the AfD’s rise (the party won seats in the Bundestag for the first time in 2017), and also the moment when Europe was becoming (or refusing to become) aware of russia’s concerted destabilization efforts against its western neighbors through hybrid tactics and information war. Timothy Snyder’s The Road to Unfreedom, published the same year, details russia’s malicious efforts in several countries, both successful and unsuccessful. Seven years on, the event Knospe explores could indeed be said to have multiplied, like her collage. Political developments have gone beyond troll armies and Kremlin handouts to right-wing candidates and turned into authoritarianism riding on the back of cynically populist victories across the world.

Photo by Olesia Saienko

In their strangely cute mutations, the works of both Rothe and Biesendorfer feel like they could be a sequel to Water Proof. In that sense, a whole chronology starts to form for me in this half of the exhibition. 27/08/18 (from 2018) gives us context for Brown Wire (the present), which sets the stage for Water Proof (the near future) and its inhabitants (the slightly more distant future). And, of course Maria (World War I) watches over, as a prequel to them all. In the gallery’s other space, across the foyer and down a short set of stairs into a notably more brutal environment with concrete and exposed conduits, are five more works. They share less of a chronology for me, but they also feel like they exist together more in the present.

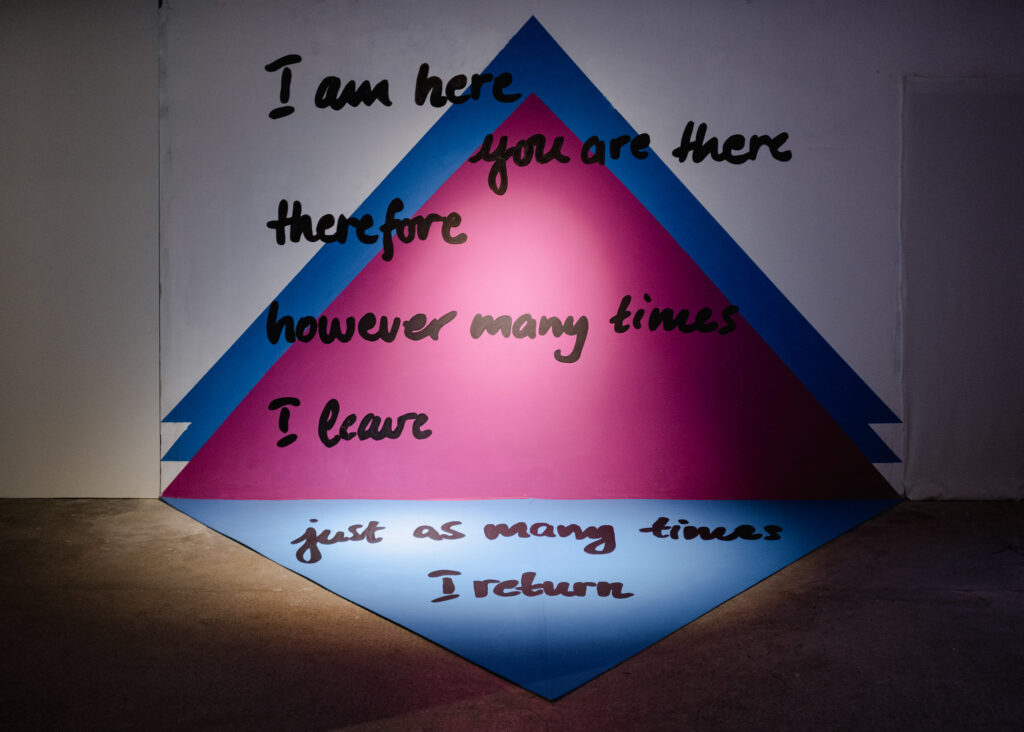

The first thing we see on entering is Flow by Saša Tatić, a mural of text with pink, white, and blue triangles. The text reads, in English, I am here / you are there / therefore / no matter how many times I leave / I return just as many times. Just as the bright colors of the piece stand in contrast to the muted and dark character of the other works, the ambiguous message seems to contrast the more dismal outlook of the show. It brings to mind Kira Muratova’s 2012 film Eternal Homecoming [Вічне повернення], sometimes called Eternal Return. The film is structured as a series of repeating screen tests, working through the same lines over and over again (in russian, which itself seems like a place difficult to return to now), to unsettling effect. The prospective pleasantness of Flow reads better for me in the space with this reminder of how repetition can turn to unreliability, tension, interpersonal strife. This subjective reading helps me grapple with the work’s opacity. I am grateful to Tatić for bringing colors, even if I see their liveliness as somewhat deceptive.

Photo by Karl Aner

Marta Dyachenko’s o.T. stands to the left of the entry way, and, with its solid cast concrete shapes and stained glass, speaks to Tatić’s colored triangles. Dyachenko uses fragments of a hotel in Kaniv, a city a couple hours south of Kyiv. The architectural fragments, presumably from the Soviet era, balance vertically. The text tells us that this “hints at the fragile but still existing possibility of creating free art without political restrictions in contemporary Europe”, a statement that, while perhaps true to the artist’s intentions, also feels like more of a self improvement “you can do it” mantra for a sick society. This, like the formal aspects, links the work to Flow, creating a diagonal of affirmation cutting across the undermining feeling that crawls through the show. Both works are effective, but I am somehow not convinced that they are doing what the curatorial text asserts they are doing. Are they overwhelmed by their surroundings? Or are they in fact sneakily discussing something entirely different, that we have yet to uncover?

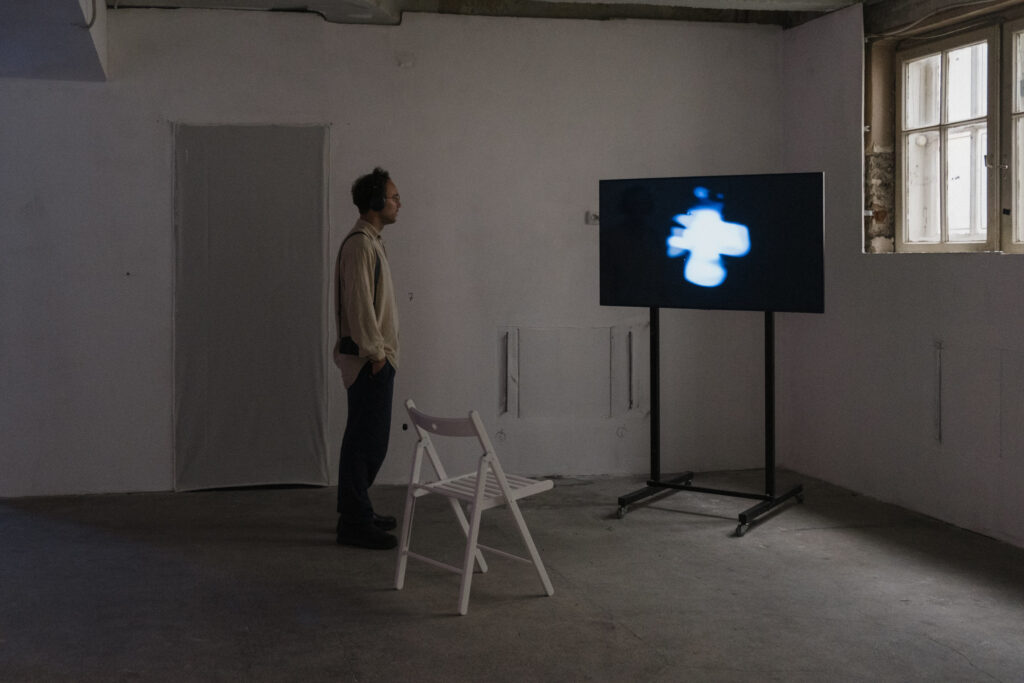

The invisible diagonal of Flow and o.T. specifically cuts across the other two works in this space, Bela Bender’s +/- and the aforementioned Kurgans, Tombs and Us. I must admit, apart from my more physical reaction to the work of Pohrebnnyk, Milyukos, and Ivchenko, my Ukrainian is not good enough to work through the piece meticulously, since it relies to some extent on text that appears to quickly on screen for my slow eyes. But the axis it shares with Bender’s work, x-ing across the invisible diagonal of Tatić and Dyachenko, is fortunately only weighted by text from one side. +/- is also a video work, an endless loop showing the surface of dark water reflecting a white light switching from + to –, as vibrations ripple the surface. The text notes that the artist wanted to comment on the use of “+” (and the world “plus”) by Ukrainian military to mean both “affirmative” and general enthusiasm, as well as its percolation into the broader culture of digital messaging, in particular its use to express satisfaction with content depicting deaths of the invaders. This makes some sense, especially considering the active merger of techno club aesthetics with military imagery in Ukraine. We’re reminded that the work’s slickness is just as incongruent as the seductive techno sheen always is when superimposed on the messiness of war. The fact that the work touches on this discomfort, knowingly or not, is a good thing.

Threshold, by brothers Pavlo and Danylo Kovach, together with Chychkan’s Maria, bookends the exhibition. Both deal with artists serving, both are bloody, both contain uncomfortable subtexts that swirl darkly under their surfaces. The work is in an adjoining concrete room. The sound of the piece hangs in the space heavily, and, as mentioned above, echoes into the rest of the pieces in the second part of the gallery. It comprises a video work projected on a section of steel fencing hung with welcome mats. In the video, Pavlo cleans the inside of a military truck. Pavlo, who is a well known figure in the artistic community as a member of Open Group and former curator of the Lviv Municipal Art Center, was mobilized a little over a year ago. He now serves in the Armed Forces of Ukraine, as we’re told by the exhibition guide “he is responsible for communicating with the families of those killed in action and missing.” The text further explains that in the video Pavlo is swabbing blood from the inside of the truck. He brings the same matter-of-fact deftness to the act that he previously brought to his performance work, making the unquestioned authenticity of his task strangely performative. Danylo, also a well-regarded artist in Ukraine, now lives in Vienna. His contribution to the work is the collection of used welcome mats. They have been taken from the doors of Ukrainian refugees in Vienna, and exchanged for fresh ones by the artist. The mats are both screen and frame for the projected video.

Photo by Olesia Saienko

Together these elements speak about the two brothers, inhabiting the two extremes currently available to men of military age in the country. This creates a work that is uncomfortably about them rather than the symbolism and performance of its composition. Within the Ukrainian art scene, conversations around male artists who have left the country and those who have been mobilized are so dense they cannot be printed, making the experience of the majority of viewers of the work non-transmissible. Layers of circumstance, choice, guilt, and consequence exist in both paths, and sink far deeper than the status updates that reach the eyes of a broader international audience. On that surface though, we can see this dense and tangled work, which discusses refugees and conscripts in the same breath. The repetitive motion of Pavlo’s scrub brush isn’t mirrored only in the feet wiped on Danylo’s welcome mats, it falls in and out of sync with Bender’s pulsing +, and Pohrebnnyk, Milyukos, and Ivchenko’s looping history. Together this produces the real difficulty with Tatić’s “return”. When she speaks of return in this room, or in this exhibition, what is she actually referring to? Her biography helps us—she is Bosnian, born in 1991—but it is still difficult to make sense of her words.

Will you be wiping your feet when you return, or will someone else be scrubbing you from the inside of a truck? Will you be a + in someone’s Telegram channel, or will you breathe the air and touch the soil of your native land once again?

In general the works, and indeed the composition of the show, chafe uncomfortably on questions of mobility. The work of the Ukrainian artists’ is haunted by their restricted movement. It is clear that the team for this exhibition knows the Ukrainian scene intimately, but it is nonetheless worth noting the asymmetry in the larger international art-curatorial complex. Karavai and Gruner may be doing studio visits in both Ukraine and at art schools in Germany, but few curators from abroad seem committed enough to visit Ukrainian studios. Indeed, if they were to visit, the scene would be very different from its German counterpart, where studios are often provided by a robust state-funded art pedagogical complex, where even mature artists are incentivised to nominally continue their enrollment by stipends, facilities, and free public transportation.

In Ukraine, artists are still sweeping up the glass and crowdsourcing funds to replace the windows after the recent attack near the Institute of Automatics, a prominent hub of studios in Kyiv. It’s not fair to say that no one is coming to visit these artists, or that there is no curatorial interest from abroad, but it is fair to say that the conditions that artists are working under are vastly different both in terms of resources, visibility, and priorities.

This fact amplifies subtext related to mobility included in the exhibition guide. The mention of Bela Bender’s “reflections and doubts about a possible trip to Uklraine—a trip that did not happen this time” is a page away from the mention that Fabian Knecht has made “around 20 trips with small shipments since the start of the full-scale war”. I’m not sure why this is here, but if it is printed in the exhibition guide, the curators must have intended it for our consideration. On the Ukrainian side there are similar indirect nods to access, mobility, and positionality. The most difficult example is found in the simplest biographical data of Pavlo and Danylo Kovach: “He serves in the Armed Forces of Ukraine” and “He has been living in Vienna since January 2022”, respectively. I want to be very clear: mentioning these points is in no way a judgement, or even a suggestion that life choices as complicated as those made during war are somehow competing for legitimacy. I routinely push back on friends in conversations that slide towards moralizing when it comes to the choices others make to engage with and survive this moment. But the tension embedded in those conversations seems very present in this exhibition, and I don’t think someone in Ukraine can view this exhibition without reading between these lines.

Just like the discomfort with mobility, it is also worth looking closer at the difficult presence of childbearing in multiple places in the exhibition. ‘Child as future’ is a cliché, but will forever be an effective one. We find it overtly in Buchatska’s game and Biesendorfer’s spoon, as well as in the biographical background in several cases—Buchatska is herself carrying a child at the time of writing, and the exhibition guide makes a notable mention that both Kovach brothers have newly become fathers. In the show, however, the timbre of the cliché is uncertain. What kind of future do we have for these children? Our present—the environment of the pregnant mother or new father—constrains our children’s path.

Photo by Olesia Saienko

And this is the most difficult aspect of this exhibition. For those of us who are not visionaries, the present constrains our imaginations, too. We get caught in the ever shortening media cycle, hoping something will turn the tide of the war, or even simply international engagement with the war, only to be strung along by fickle politicians and corporate interests, over and over again. In my better moments, I resist this emotionally exhausting treadmill, and try to look to people who can see something that I can’t, some kind of possibility of life, growth, change in the midst of this unprovoked misery. For me, the visionaries are artists, and I turn to them and their work for lessons in faith. Faith is the practice of believing in a future, even if the present does not support that belief. Faith that Ukrainian victory will come underlies—and must underlie—all creative activity in the country at the moment. So what are we to do, when we turn to the visionaries—the artists—and their vision, at least when assembled together into an exhibition asking “where does it all go?”, turns out to be even darker than our current circumstances?

This show, more than is usual, speaks from behind the works. Backstory, curatorial methodology, personal practices all say something about the individual works and the path towards their convergence here, now, in Asortymentna Kimnata.

However, that is the past, and as an assemblage, the exhibition projects a future—where it all goes. And it is this projected future, not the past or present, that weighs on us.

In Ukraine, it is self-evident that the present is difficult, ever narrowing, even catastrophic. But what responsibility does each of us bear for projecting that catastrophe into the future? What responsibility do we have to defy it? I ask this with full acknowledgement of my place here—it is not my country facing existential invasion, so how can it be my responsibility to demand faith in a brighter future from those facing it? But when we ask what the perspective of an art exhibition can do, can we ask for accountability if the future it proposes is something we do not want to see? Maybe that future is even something that the curators themselves defy, just by being here and making this show. So is this where it all goes?